NOTES FROM THE FIELD

Once in a long while, I enter the world of Facebook Comments to get a feel of the place. It can be maddening, but as a writer I find it helps periodically to exercise muscles that I rarely use in normal social settings. So, for the past 24 hours, I’ve been spending more time in Zuckerberg’s playpen than on Netflix, which for me is saying a lot.

The timing had to do with pieces that I wrote last week, in midweek and yesterday morning criticising some worrying developments in online politics. These generated pushback from individuals who, for some reason, took it very personally.

Engaging them was as instructive as I’d expected.

One striking pattern in their comments was the dogged effort to change the subject away from the matter I’d raised: the extraordinarily embarrassing sight of a group of PAP fans publicly accusing PAP stalwart Inderjit Singh of being a Chinese Communist Party stooge. No, this isn’t what ownself-check-ownself is supposed to look like. To call it an own goal doesn’t do it justice either. It’s more like executing a standing double backflip while kicking oneself in the head.

Rather than quickly deny, disown and limit the damage from what’s apparently a rogue skunkworks unit, the PAP seems content to perpetuate the impression that its radical fringes will be given free rein to police insiders who inch out of line. Sort of like how Red Guards in the Cultural Revolution were — and CCP trolls still are — let loose on internal critics.

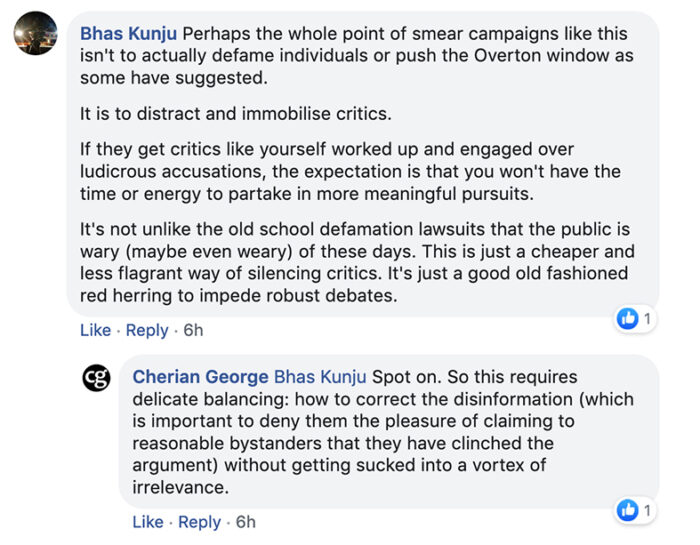

Pointing this out has infuriated some hardcore PAP loyalists, who swarmed Facebook to attack the messenger and other non-PAP critics. They naturally avoided talking about Inderjit Singh, crossing their fingers that the internet will just forget. And, as one astute writer pointed out:

The second lesson I’ve gathered from the exchange is not new, but a powerful reminder of just how toxically partisan our political discourse has become.

Ours is a multiparty democratic system (in principle; in practice it’s a dominant party system). So a certain amount of partisanship is inevitable. But if citizens are only capable of viewing debates through a party-political lens, that’s a serious problem. Democracies progress when governments and citizens deal with ideas and arguments as they stand, and not through the lens of fixed allegiances or the short-term need for partisan point scoring.

I won’t address their ad hominem attacks and sheer inanity, because I always feel it’s more educational to engage with opponents’ arguments at their strongest — no matter how hard that is locate — and not their stupidest. So let me focus on the nub of the hardcore PAP loyalist counter-arguments: it is basically that I should be more cognisant of the fact that pro-opposition trolls are at least as bad as pro-PAP ones, and that my failure to be even-handed betrays a bias.

One prominent pro-PAP blogger even emailed me just before midnight last night to share a sample of the vulgar and xenophobic messages he’s received from anti-PAP sources. He promises to “save the long form for elsewhere” so I won’t steal his thunder by sharing his email and attachments here.

There are at least three ways I can respond to this argument: the personal, the structural, and the ethical.

The first requires me to point out my own record as a writer on Singapore politics. I find this is a somewhat tasteless exercise, because I think readers should be able to judge an argument on its merits, without reaching for the intellectual crutch of making up their minds based the speaker’s perceived background (for fellow nerds: this is in line with the theory of deliberative democracy). But I recognise that in the real world, if we don’t play the game and guard our credibility by referring to facts, we lose out to bad-faith opponents who will attack our credibility based on lies.

So I have to point out reluctantly that I have a long history of calling out idiocy and abuse on the opposition side of cyberspace. As a result, I have been trolled by pro-opposition types for far longer than by the Johnny-come-Latelies of the PAP.

I was, for instance, targeted by opposition trolls around the 2011 election, when I criticised the misogynistic attacks on the PAP’s young new candidate, Tin Pei Ling. I was also targeted by The Online Citizen when I pointed out that they had unfairly triggered a witch-hunt against another PAP backbencher by misquoting him. Netizens also attacked me when I suggested that bloggers (all whom were non-PAP back then) create and abide by a voluntary code of ethics.

In my 2017 book, Singapore, Incomplete, I have only one chapter (republished in my latest compilation, Air-Conditioned Nation Revisted) that focuses on irrational, intolerant online public opinion — and it’s not about PAP trolls. It is about the anti-government netizens who launched a xenophobic onslaught on a proposed Philippine independence day celebration, exploiting anti-immigrant feelings to attack the PAP government’s immigration policy. I still think this 2014 episode represents the most shameful low point in Singapore’s history of online discourse.

Many opposition supporters also did not like it when I threw a wet blanket on the opposition’s famous triumphs in the 2011 General Election: within hours of the result, I predicted that a much-improved PAP could make the opposition’s job much harder, which is exactly what happened in 2015.

For at least the past five years, I have made a conscious effort to focus my writing on how to improve the PAP because, as I have openly stated and still believe, it would be foolish for reform-minded Singaporeans to put all eggs in the opposition basket.

If we want a better Singapore, working for a better PAP must be part of our total strategy. Yes, we need stronger opposition as an alternative, but that does not mean the health of the party in power is of no consequence. After all, even if you have taken out a life insurance policy on your head of household, that doesn’t mean you should stay silent when he picks up bad habits like smoking. My 2017 book was entirely premised on this conviction: we need to improve the PAP in case the opposition doesn’t develop into to a viable alternative. Hardcore opposition fans, naturally, do not like this way of thinking.

Now that this is out of the way, let me deal, second, with the structural issue. In any democracy, the words and actions of a ruling party matter more than the words and actions of the opposition. This is even more true in Singapore’s dominant party system, where it is unlikely that the opposition will take over any time soon.

It is correct that we demand higher standards from any ruling party, because that’s where real power resides. Not just influence, and not just words, but cradle-to-grave powers to tax and spend, to licence and lockdown businesses, to issue orders enforceable by police, and to decide how children are educated, where to bury the dead and when to exhume them, and even when to send our men and women to war.

Our Constitution is based on this principle, that rulng parties have special obligations. Which why Lee Hsien Loong is answerable to Parliament in ways that Kenneth Jeyaretnam is not. PAP fanatics who say government critics are biased because we don’t spend equal time scrutinising the opposition may as well accuse the Constitution of double standards. This seems like such an obvious point that to belabour it risks insulting the intelligence of most readers. So I will stop here.

Third, there’s the question of values and ethics. In every sector, the best organisations set their own standards and brand themselves by their values. They don’t benchmark against the average, let alone the lowest common denominator.

Nor do they engage in whataboutism: when it’s pointed out to them that they are being associated with bad behaviour, they don’t say, “But what about our competitors? They are even worse.” No. If they are not responsible for that bad behaviour they disavow and clarify. If they are responsible, even indirectly, they accept responsibility and take swift remedial action. For example, when loutish football fans get abusive and this is picked up by TV cameras, top clubs don’t make excuses like, “We didn’t instruct those fans to do that, so don’t blame us.” No. They say, “Such behaviour is not who we are. They are not true fans, do not represent our values. We reject it completely and unequivocally.” Many socially responsible media organisations have the same attitude to readers who post comments. The best news publishers understand that abusive and irrelevant comments taint their brand and reduce its appeal, even though they were not written by the organisation’s own staff. This is why many such sites close comments on topics that they know will bring out the worst in readers.

Compared with football clubs and media organisations, it is much more important that political parties pay attention to the reputational damage caused by their hardcore but misguided fans and followers. Political parties set the tone for our democratic life. The serious ones should be eager to clean up their act.

Not surprisingly, some are quick to claim that such calls for ethical behaviour are the same as demanding censorship. The loudest objections tend to come from the worst abusers who have most to lose from higher standards. Therefore, when I called for voluntary self-regulation about a decade ago, I was derided by anti-government forces. Now it’s the turn of the vocal, nutty minority of pro-PAP netizens.

But let’s see how the more reasonable and quieter majority responds. And no, I won’t be looking for them in Facebook Comments. As workouts go, it is like jogging in circles. You break a sweat, but don’t go anywhere.

Comments are closed.