SECTION 298 IS RIPE FOR REVIEW

The government has said it’s ready to rethink how Singaporeans should be allowed to discuss the sensitive topics of race and religion. If indeed we are going there, we need to add Section 298 of the Penal Code to the reform agenda.

This is a bad hate speech law, because it fails to distinguish between:

• the objective harms caused by incitement to hate — which violate victims’ equal rights, and should therefore be criminalised; and:

• words that cause subjective offence and disharmony — an allegation too hard to counter and too easily used to silence socially valuable speech, and which should therefore be regulated through social norms, not hard law.

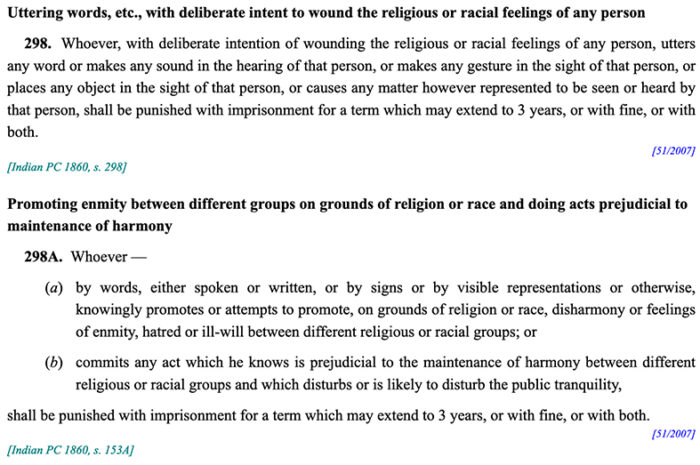

For the unacquainted, here is what the law says:

It is a law with roots in British colonial times, devised by rulers more concerned about taming native subjects than building a multicultural nation. It does not belong among Singapore’s multiple defences against chauvinism, communalism, and hate. It promotes offence-taking instead of live-and-let-live tolerance. It encourages citizens to demand action from above, instead of talking things through among themselves.

Until now, I felt it was futile to press this point, because most Singaporeans are wedded to the idea of solving social frictions by calling 999. I did broach the topic in a Straits Times op-ed way back in 2011. But my 2016 book, Hate Spin, was global in scope and barely referred to Singapore. When I brought up Section 298 in my 2018 Select Committee testimony, it was because I felt I had to, not because I expected it to make any difference.

This week, though, I’m starting to wonder if Singaporeans are finally ready to reconsider their law-and-order approach to managing diversity. During an Ethos Books dialogue on Sunday, Mohamed Imran Mohamed Taib, one of Singapore’s wisest thinkers on race and religion, made an interesting observation about the PAP’s attack on Raeesah Khan and how it backfired.

He was of course referring to one of the biggest controversies in this month’s election campaign, when someone lodged a police report against the Workers’ Party candidate concerning intemperate remarks she had made in the past about the system being rigged against minorities. She immediately apologised, but the PAP went to town with this. It issued a party statement that inaccurately claimed that she had by her own admission made anti-Chinese and anti-Christian comments.

Not just die-hard opposition supporters but also many apparently middle-of-the-road Singaporeans reacted strongly against the PAP attack. The blowback was strong enough for PAP leader Lee Hsien Loong to change the party’s tune on the final night of campaigning, acknowledging that younger Singaporeans like Raeesah might have a different approach to talking about race.

On Sunday, Imran said, “There was a clear backfire over the police report on Raeesah Khan. … With the outpouring of support for Raeesah Khan, does is it mean that people are more accepting of divisive racial or religious remarks? I don’t think so. What clearly happened is this – people now have greater sensitivity about when race or religion is weaponised for political ends.”

This is a healthy development, Imran added. It suggests that people have internalised the government’s injunction against politicising race and religion. What is new, he suggested, is the people’s awareness that the taboo should also apply to those who claim to be policing harmony.

“It cuts both ways. Saying something is divisive can itself be a divisive act with an intentional political end. This is something we have not seen before, which clearly speaks to greater civic political awareness.”

If Imran is right, Singaporeans are now savvy enough to understand that legal interventions designed for ostensibly good ends can be hijacked for bad ones. If so, we may be ready to talk about Section 298 as well as other similar laws.

The law is again bound to make news soon anyway, since the PAP’s offer of a truce to Raeesah’s fan base did not resolve the matter of the police complaint. The authorities will have to announce the outcome of their Section 298A investigation. My guess is that, rather than charging her, she will be let off with a “stern warning” — the route they usually take when the offender has shown remorse. This will defuse the debate about the law itself, until the next time it is wielded.

Even if Raeesah is spared, though, Section 298 should remain in the dock, to be grilled about its actual contribution to Singapore’s system of managing diversity.

Such discussions are easily side-tracked and waylaid, so some clarifications are in order.

First, this is not a partisan issue. This time, the law was weaponised by PAP supporters against an opposition politician, but strategic offence-taking has also been used against the PAP by its critics, as I pointed out in a 2016 journal article on incitement and offence laws in Singapore and Indonesia.

Second, it would be naive to think that the Sengkang GRC result shows that playing the race or religion card no longer works. Although there was an outpouring of support for Raeesah on online forums, there is no hard evidence that the PAP’s tactic – casting her as anti-Chinese and anti-Christian – did not have an impact at the ballot box.

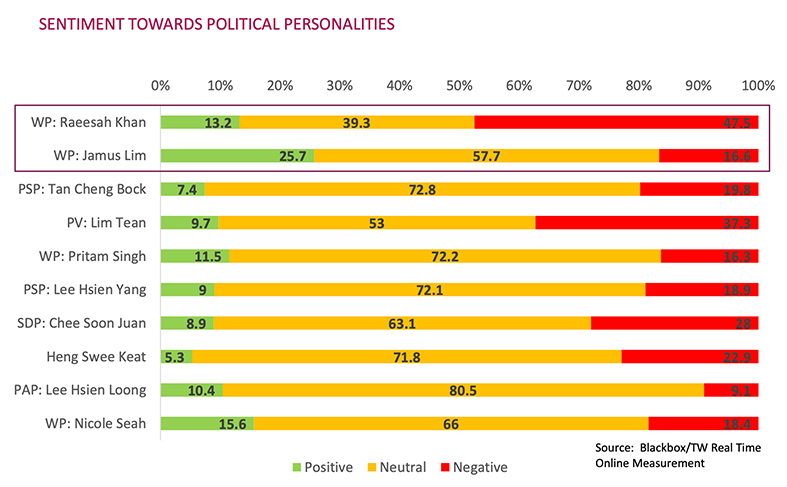

Online sentiment analysis, though hardly an exact science, showed more “negative” perceptions about her than even Chee Soon Juan, who has been subject to far more intense and sustained attacks.

So it is quite possible that Raeesah owes her Sengkang GRC seat not to #IStandWithRaeesah, but to her wildy popular teammate Jamus Lim. All we can say with certainty is that the anti-Raeesah smear campaign was not effective enough — not that it didn’t work at all. In a single seat or in a different GRC contest, the PAP campaign could well have tilted the balance against her. I point this out not to rain on her parade, but lest we misinterpret her party’s electoral breakthrough as a sign that Singaporeans are immune to Islamophobia.

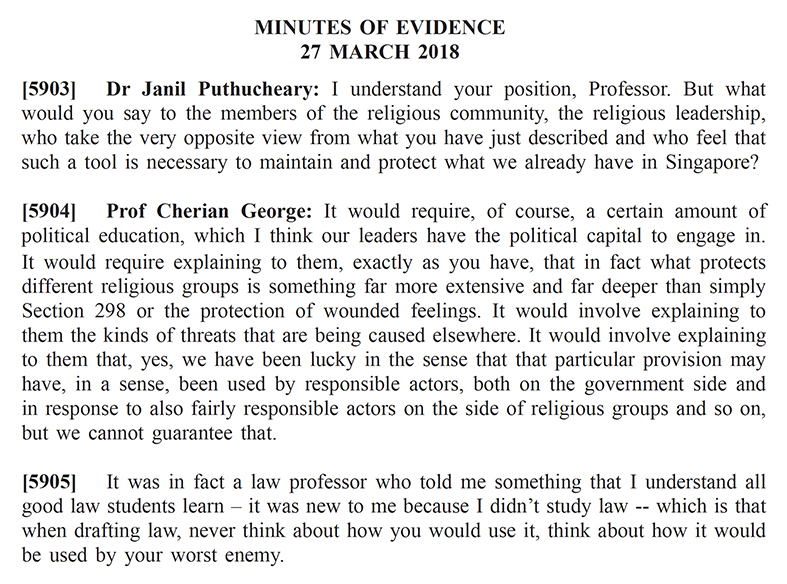

Third, most Singaporeans who are rightly protective of racial and religious peace need to be convinced that reforms won’t generate unacceptable risks. As Janil Puthucheary asked me during the Select Committee hearings when I proposed repealing Section 298: “But what would you say to the members of the religious community, the religious leadership, who take the very opposite view from what you have just described and who feel that such a tool is necessary to maintain and protect what we already have in Singapore?” The answer I gave is below:

The conventional wisdom is that if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. And indeed if by “broken” we mean prone to communal violence, Singapore is in good shape. I suspect, however, that many Singaporeans share my view that we can aim higher than not killing one another; that we can be so bold as to aspire to our “one united people” pledge. It will take a long process of gentle, evidence-based persuasion to wean our fellow Singaporeans off their dependence on the police.

Finally, if the political leadership does not warm to the idea of reviewing the law, we should expect that the status quo will be vigorously defended by PAP Ultras — the internet brigades that in recent years have stolen the mic from the establishment’s voices of reason, spewing divisive rhetoric from the national populist playbook of rightwing extremists around the world. They will be back, preying on ordinary Singaporeans’ fears of instability, spreading disinformation about anti-racism activists, and thus trying to paralyse any effort for progressive change.

I hope Imran is right, that Singaporeans are wisening up to political dirty tricks. If so, it may indeed be possible to have a meaningful debate about how to amend Singapore’s racial harmony laws.

Correction: An earlier version said that allegations of offence were “too hard to prove”; I meant too hard to disprove/counter, and have amended the text accordingly.

Comments are closed.