TIME FOR A CODE OF CONDUCT

Some pro-government websites are going too far, violating principles set out by the Select Committee on Deliberate Online Falsehoods.

Singapore needs a code of online conduct for all political parties and government bodies, committing them to more ethical and transparent use of internet tools. Public opinion manipulation by politicians, their functionaries, and their hardcore supporters is threatening Singaporeans’ ability to conduct reasoned debates about national issues, and exposing individual citizens to the harms of hate speech.

Like anything on the internet, such toxicity cannot be regulated out of existence, nor need we even try. But self-regulation by major political parties as well as the internet user with the loudest voice — the government — can go a long way towards cleaning up our political discourse.

There are at least three key core commitments that a code of conduct could flesh out:

- No to all inauthentic behaviours, such as using fake social media accounts and paid human trolls to mislead people about the state of public opinion.

- Yes to full transparency in public communication, with no hidden or opaque sponsorship of content, or use of anonymous sites.

- No to supporters who propagate lies and incite hatred in your name: disown or correct those who abuse others, including your political opponents.

Instituting such a code of conduct is a major piece of unfinished business arising from the deliberations of the 2018 Parliamentary Select Committee on Deliberate Online Falsehoods.

The Select Committee’s report expressed concern about these and other tools: fake social media accounts to infiltrate communities and amass support; human trolls and automated bots to make falsehoods go viral; and digital advertising tools and for-profit political consultants using data analytics to micro-target messages at susceptible demographics.

On transparency, the Select Committee endorsed several experts’ recommendation to compel disclosure about whether content was paid for, and by whom. This transparency should be required of all forms of issue-based messaging, and not just campaign advertising, it said. “The goal of such transparency is to educate users on the behaviour and intent of other content providers they encounter online, and reduce the opportunity for malicious actors to hide behind Internet anonymity to carry out abusive activities,” the Committee said.

It added: “Users ought to be provided with sufficient information to know whether they are interacting with accounts belonging to and managed by a real person, or whether they are interacting with accounts run by a bot, or with an account where someone is impersonating another. Impersonation is often used to create an appearance of popularity, to increase the influence of the online falsehoods propagated by inauthentic accounts. This is not a trivial concern; inauthentic accounts operating on a broad scale have the potential to disseminate widespread disinformation.”

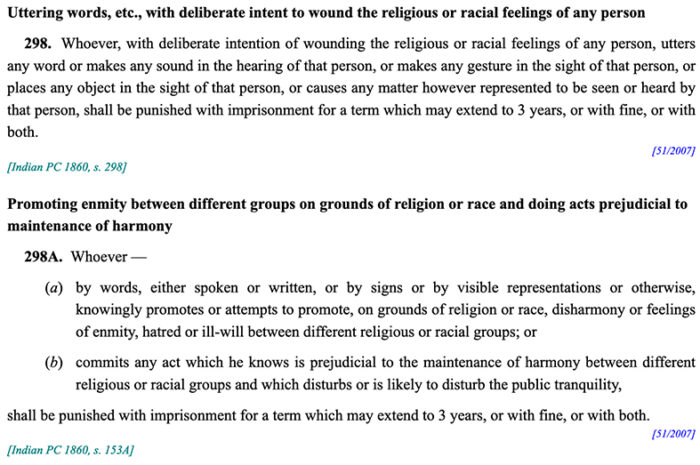

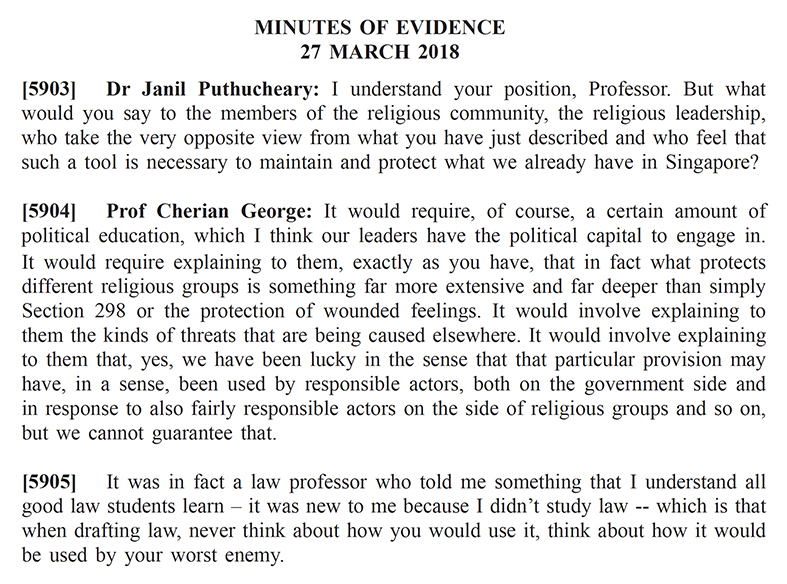

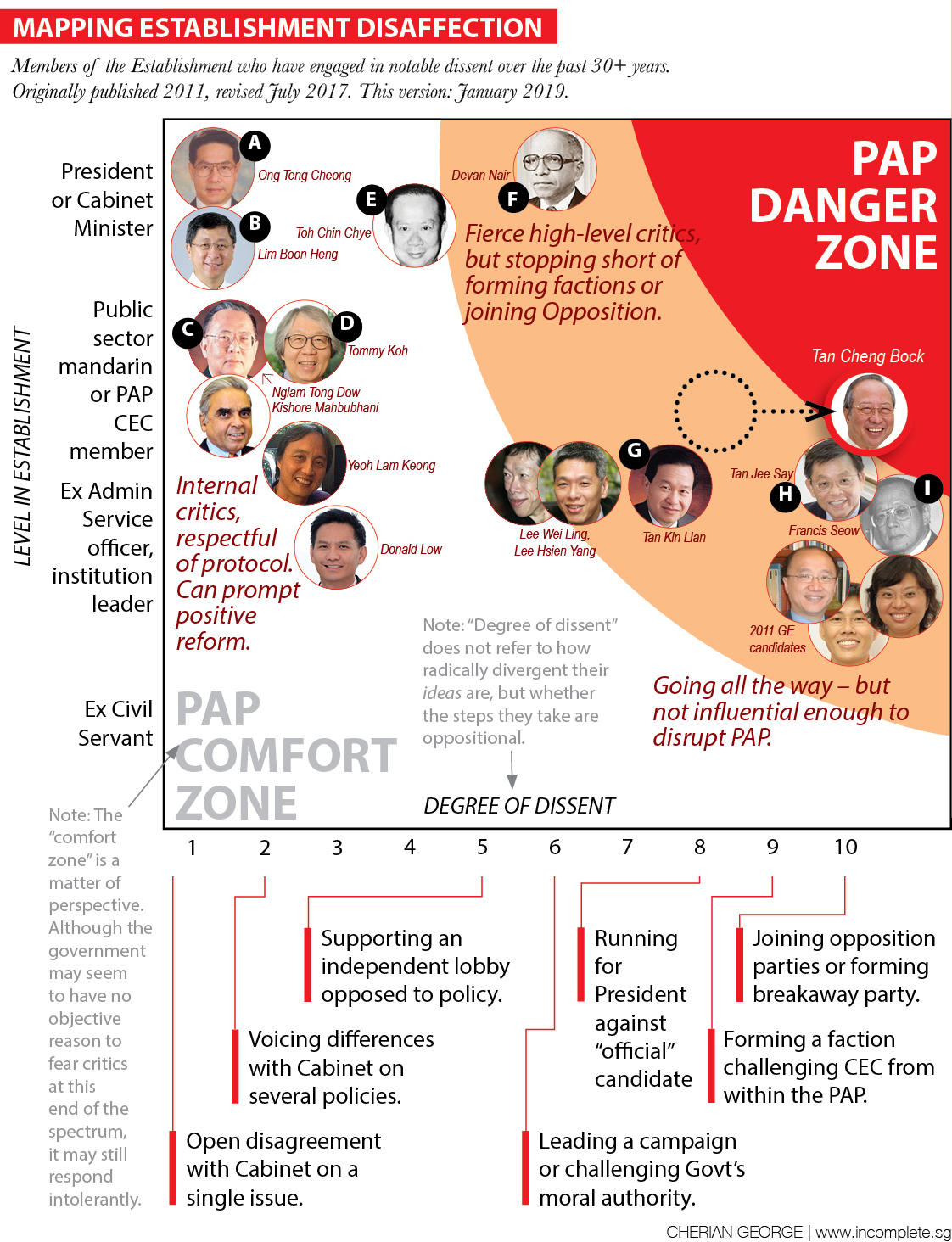

Select Committee Hearings, 2018.

But, there was a major problem with the Select Committee’s report. It was like a large illuminated mirror giving us a better look at our online environment — but tilted at an angle to keep the government out of view. After setting out key ethical principles for online public discourse, it recommended their imposition on everyone else, especially internet platforms such as Facebook, but not on the state or the ruling party.

This seed of selective vision ultimately sprouted into the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (Pofma), through which only government ministers get to trigger a correction or takedown order — as if it is inconceivable that any current or future office holder would ever be guilty of a false or misleading statement of fact.

A year since the passage of Pofma, it is time to make up for that blind spot in internet regulation.

Watching the watchers

Many Singaporeans will find the idea of holding the government accountable for its own speech quite radical. They trust that the government will act as a responsible policeman who does not need policing. This helps explain why Pofma was met with indifference and even positive support by the general public.

It is true that many extreme forms of disinformation are likely to come from overseas: agents of the People’s Republic of China trying to prise Singapore out of America’s sphere of influence; India’s Hindutva nationalists sowing hatred against Muslims; our neighbours’ radical Islamists preaching religious exclusivity and intolerance; and Fox News selling its MAGA worldview, along with bleach and malaria medication as treatments for the “Chinese Virus” (why the Temasek-controlled Starhub CableVision persists in giving Fox a perch in Singapore continues to confound me).

But we should not confuse extremity with impact. Low-grade manipulation by the powers that be can have a more pernicious influence than foreign or fringe attacks. Decades of research on media effects tell us this. And hate speech jurisprudence around the world is based on this insight: the European Court of Human Rights, for example, considers not just what is said but also who is saying it and in what context. Party leaders are held to a higher standard because they are more likely to incite harm than, say, a blogger or poet without a big following.

We also know from more recent research that the questionable methods of right-wing populist movements have gone mainstream, with more and more centrist governments deciding that if you can’t beat them, join them. In Indonesia, for example, President Joko Widodo’s camp has invested in the same tools of online persuasion as his less palatable foes. A report by the Oxford Internet Institute last year confirmed that governments are emerging as major players in social media manipulation.

Singapore was not included in the 70-country Oxford study, and although we do not lack individuals with the skills to undertake the required forensics, the ones with the time to do it mostly work in universities and other research centres subject to political constraints. We can surmise that Singapore, a global pioneer in e-government, is probably not falling behind in computational propaganda. Beyond that, most of what we do know is anecdotal. Many seasoned netizens are able to tell you if someone criticising you on Facebook is a good-faith interlocuter, a troll, or a fake account. One giveaway is to check the account’s history. If it has only three posts and five friends, it was probably made up just for the occasion — the digital equivalent of out-of-towners bussed in to beef up an election rally audience. But to make such fraud harder to detect, the operator can buy or hijack established accounts. High quality social media manipulation is expensive, which is why states do it better than fringe groups — and why many governments are no longer cowed by the internet and believe this is a war they can win.

Studies in other countries also tell us that computational propaganda involves a division of labour among various kinds of actor. At the centre of the enterprise is usually the ideological machinery of the government or party, churning out major talking points and identifying threats that need to be neutralised. The hub would also include a professional IT arm and data analysts, plus a media team to create content for a leader’s Facebook page, for example.

But a large volume of social media postings usually come from a separate layer of diverse players acting with considerable autonomy, including organisations and individuals affiliated to the party, and private websites covertly funded by the regime. Also craving a piece of the action are for-profit PR consultancies, often using foreign expertise. Governments and parties outsource some of their online operations to these mercenaries, who then marshal bot armies and engage in other dark arts at an arm’s length from their clients.

Finally, the most populous category in most countries comprises the unpaid volunteers who enlist in the cause out of conviction. Many of them may be trying sincerely to add value to the marketplace of ideas, but others have the self-awareness and social graces of a three-year-old (no offence to toddlers). They pick up on their leaders’ dog-whistles, share disinformation created by IT cells and PR consultants, and disrupt serious conversations with their tribal war chants. They believe they are doing god’s work, failing to realise that they themselves are victims of opinion manipulation.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is a major user of computational propaganda.

Worrying trends

In recent years, Singaporeans engaged in public debate have voiced alarm at the ratcheting up of intolerant national-populist rhetoric by the PAP. Supporters defame critics, claiming they are foreign-funded fiends who are threatening the country. For an academic like me, studying major hate movements around the world, I find their faint echoes in Singapore chilling. Government leaders have not taken this trend seriously enough, allowing their followers to continue believing that political opposition and independent journalism are equivalent to treachery and treason.

Last week, a particularly vile attack came from a pro-government Facebook account named Global Times Singapore (GTS). It was obviously reacting to a strongly-worded opinion piece by Sudhir Thomas Vadaketh in Hong Kong’s South China Morning Post (SCMP). GTS charged that Sudhir, along with other Singaporeans who have written for the paper — Ken Kwek, Tan Tarn How, PN Balji, Inderjit Singh and Donald Low — were contributing to a campaign by China to put pressure on Singapore. GTS defamed my wife, a senior SCMP editor, by suggesting that she is not acting professionally but using her position to help China put pressure on our country. It also defamed me, suggesting that I was instrumental in helping China by channeling these Singaporeans — two of whom I have met only once, maybe three to ten years ago — into my wife’s hands.

The allegation was so outlandish that most of us had a good laugh. Singaporeans who follow current affairs will recognise all the writers I’m alleged to have recruited for SCMP as belonging to the 95th percentile of the country’s independent thinkers, and therefore singularly unsuitable candidates for any conspiracy. They will also know that the one and only reason why so many of Singapore’s best commentators have resorted to SCMP as a forum for their pieces is that Singapore’s throttled newspapers tend to be inhospitable to views deemed critical of the government. Singaporeans who follow the media in other parts of Asia and the world can also guess why the PAP and its hardcore supporters are so thin-skinned about critiques that open societies would consider mild. It must be because decades of tightly managed debate have acclimated officials to a public sphere suffused with friendly white noise, rendering them hypersensitive to the rare instances of robust criticism.

Although it is easy to ignore the Global Times Singapore post and move on, there are three reasons why we should insist that the government take such episodes seriously. First, they have the potential to cause harm to individual citizens who are so targeted. Several incidents around the world show that all it takes is a single nutcase to get fired up by a conspiracy theory before violent retribution is meted out against defenceless individuals. My wife and I have positions of responsibility in Hong Kong’s highly polarised spheres of media and academia respectively. Both these arenas have seen cases of individuals being targeted for vigilante violence after being branded as too pro-China or too anti-China. We felt safe knowing that nobody looking at our work could honestly label us as either. We did not expect to have to worry about disinformation from our own country exposing us to hatred and contempt.

Second, there is a cost to the public interest. Don’t take it from me. Take it from the Select Committee report. “Online falsehoods can derail democratic contestation, and harm freedom of expression,” it said. “Falsehoods can erode people’s trust in authoritative sources of information, which provide a foundation of facts for rational discourse. Psychological research has shown that being exposed to large amounts of misinformation can make people stop believing facts altogether, and decrease their engagement in public discourse.” The Select Committee also expressed concern about the proliferation of online news sources that “do not apply standards of professional journalism”. It identified public education and quality journalism as key pillars of nurturing an informed public. In Global Times Singapore, we see an archetype of a disinformation site attempting to undermine educators and professional journalists. The government needs to tell us if sites like this are excused from the principles and recommendations offered by the Select Committee, just because they are pro-PAP.

Third, there is also a cost to Singapore’s ruling party. I am not a PAP member, but if I were, I would be outraged at how pro-PAP sites are tainting my party’s hard-earned reputation for rational and sober governance. I would remind the party’s third and fourth generation leaders that Lee Kuan Yew, while always mindful of the popular will, resisted the populist temptation. I would advise them that people know you by the company you keep. Netizen Lee Kuan Yew would have remembered this, and not compromised his brand by liking or sharing comments from shady commentators sucking up to him. He would not have allowed the clarity of his message to be clouded by duffers and fools claiming to love him and hate his opponents. If my party leaders bristle at my counsel and prefer to surround themselves with sycophants and cheerleaders, I would know this is the beginning of the end for my beloved PAP.

Like he would care.

Of course, one could argue that sites like Global Times Singapore do not speak for the government, which therefore has nothing to account for. It could be an independent volunteer outfit inspired, but not coordinated nor endorsed, by any government or party official. Or it could be the product of a rogue sub-contractor of a third-party contractor of an official arm of the state. It could even be an anti-government operation disguised as pro-government in order to give the PAP a bad name (creating imposter sites is a well-documented Russian disinformation tactic). Since we do not know its provenance, it is premature to blame the government or the ruling party for it. But, whatever its origins, it is not unreasonable to expect leaders to tell us where they stand.

Time to take a stand

Granted, the online conduct of opposition supporters is often worse. But such counter-arguments belong in the realm of partisan politics, not the public interest; they are forays into whataboutism, not moral reasoning. Regardless of what others are doing, leaders have a responsibility to set the tone for their followers, and to correct those who claim to be their supporters when they are wrong. Singapore’s ruling party has a greater moral responsibility than the rest, because of its supersized influence. Just as Donald Trump is rightly chastised for being slow to condemn racism in his ranks, citizens should demand that Singapore’s political parties check the excesses of their hardcore supporters.

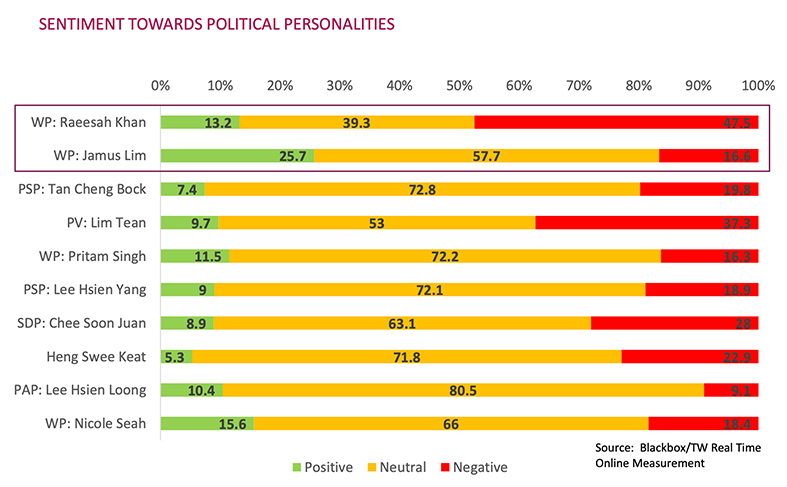

When such ugliness reaches dangerous levels on the anti-PAP side, I would apply the same standard. Correction: I have done that already, back in the days when I blogged more regularly about Singapore. In the 2011 general election campaign, for example, I was among the first commentators ordinarily critical of the government to decry netizens’ personal attacks on the debutante PAP candidate, Tin Pei Ling. I accused the anti-government Temasek Review of corrupting the political terrain with its report on Tin, even though I was rooting for her National Solidarity Party opponent, Nicole Seah.

The same year, when PAP backbencher Seng Han Thong made a racially clumsy comment about Malay and Indian MRT drivers and rightly apologised, I chided The Online Citizen for triggering a witch hunt against Seng by misreporting what he’d said. The influential alternative website, obviously stung by this criticism from an ally, painted a target on my back, for which I had to endure attacks from others in civil society.

Thus, I know first-hand that it is not easy to break ranks, defend opponents, and criticise allies when they behave like bullies. But, with that experience, I also know that it is not asking too much of elected representatives to do the same. There may be a short-term cost, but reinforcing basic norms will strengthen your spine and your movement in the long term.

So, I am listening out for what PAP leaders might have to say about Global Times Singapore. There is a higher chance than usual that such a statement would be forthcoming in this particular case. That’s because one of GTS’s targets, Inderjit Singh, happens to be a former PAP backbencher, and the Prime Minister’s GRC teammate to boot. Witnessing one of their own set upon by a rabid dog howling its devotion to the PAP cannot be a pleasant sight for PAP parliamentarians past and present. The leadership will need to comfort its own ranks — even if it wants to brush aside the wanton attack on nobodies like my wife and me.

Sometimes the internet forgets.

But a one-off, ad-hoc response is not enough. Populist nationalism has become endemic within the PAP. The party needs to draw a line for all to see.

An online code of conduct for political parties is not a new idea. Britain’s Labour Party, for example, requires all its members to abide by a Code of Conduct that includes a Social Media Policy. It expects members “to treat all people with dignity and respect”. Here’s more:

- We should not give voice to those who persistently engage in abuse and should avoid sharing their content, even when the item in question is unproblematic. Those who consistently abuse other or spread hate should be shunned and not engaged with in a way that ignores this behaviour.

- We all have a responsibility to challenge abuse and to stand in solidarity with victims of it. We should attempt to educate and discourage abusers rather than responding in kind.

- Trolling, or otherwise disrupting the ability of others to debate is not acceptable, nor is consistently mentioning or making contact with others when this is unwelcome.

- Anonymous accounts or otherwise hiding one’s identity for the purpose of abusing others is never permissible.

Obviously, such codes are never watertight. In any large community or organisation, no matter how loudly it proclaims its norms, there will always be some who deviate. That’s understandable. What matters, though, is how the group responds when its norms are violated. Do leaders “challenge abuse” and “stand in solidarity with victims of it”, to quote the UK Labour Party’s code? Or do they excuse or even tacitly endorse the abuse when the target is a critic or political opponent? How a leader responds to bad behaviour by its followers will define the character of the group; and reveal the measure of the man.

The ruling party and the government can demonstrate its stature by instituting a comprehensive internal code of conduct against online abuse that prioritises openness, transparency and honesty. We should expect nothing less from leaders who have pontificated about online toxicity as if it is the greatest threat to Singapore since Japanese bombers entered our airspace, and have gone on to construct the world’s most elaborate law against manipulation of online discourse — by anyone outside of government, that is.

But neither should we wait for politicians to act. A code of conduct can be a citizen initiative. We have enough expertise in technology, internet regulation, law, media ethics, and other relevant areas to produce such a code. And if political actors do not want to be part of the process, that itself tells us all we need to know.

Postscript, May 11

Friends tell me Global Times Singapore responded to the above (kind of). I don’t propose to reply to their eight anonymous administrators, because my issue is with the political masters they think they are serving, not the low-level functionaries operating such outlets (so low-level it didn’t occur to them that they might embarrass the Prime Minister by labeling his former GRC teammate as a PRC stooge: yes, Inderjit Singh, who served in the PAP grassroots from 1984 and as an MP for 18 years).

Why anonymous pro-PAP sites choose to remain anonymous is an interesting question. I have in the past engaged in dialogue with pro-PAP bloggers who have enough spine to reveal their identities. But the nameless variety is a different species altogether.

In Singapore, all other things being equal, being pro-PAP entails much less risk than being neutral or anti-PAP. Yet, all the critical voices that these pro-PAP attack dogs target have enough backbone to use their real identities — even the women who, global research shows, get trolled much more viciously than men.

So what is stopping these pro-PAP sites from saying who they are?

I suppose one reason is that anonymity shields them from defamation suits. Their political heroes use defamation law as one oracle to settle debates. But these sites don’t want to play by those rules — since this would require them to confine themselves to allegations that they can substantiate. (In the case of GTS, I have openly declared that they have defamed me.) I love the chutzpah of these types, carrying on the debate with such verve even though it’s obvious they can’t put their money where their mouth is.

Another possible reason why they insist on being anonymous is that they are civil servants, engaging in conduct they know violates PSD rules. A third possibility is that they are private sector hacks whose contracts require them to shield their clients from liability. It is also possible that several of these anonymous sites are being churned out from the same small factory (because, of course, efficiency is important): content producers trying to make people believe that Singapore is full of their kind. Revealing themselves would shatter the illusion.

And of course none of these suspicions makes the PAP look good, which is why I cannot understand the establishment’s tacit approval of such practices. Transparency and a code of online conduct would solve the problem.