SINGAPORE’S MYSTIFYING POLITICAL SUCCESSION

Published in New Mandala.

Published in New Mandala.

If the letter of Lee Kuan Yew’s final will is not honoured, at least its spirit should be.

The Lee family feud is a test of Singapore’s political maturity. The first step toward dealing with this highly polarising debate is to acknowledge its complexity. This is not a multiple choice question with a clear right and wrong, no matter how convinced each side is of its own arguments.

And although 38 Oxley Road is just a house, it is not just a space; it is a place, invested with meaning by a family and a nation. If we treat places like mere spaces and subject them to cold calculation, we’ll rob them of emotion and memory, and lose a bit of what turns a collection of people into a community. We need to approach the matter with open hearts and minds.

Furthermore, Lee Kuan Yew’s own views about legacy and governance do not make it easy to come to a consensus about what to do with the house. On the one hand, we have on record his strong personal desire that the family home be demolished. It’s not hard to understand how determined two of his children, Lee Wei Ling and Lee Hsien Yang, are to fulfill their parents’ wishes.

But on the other, the system he built never allowed individual preferences to stand in the way of the public good, as interpreted by the government of the day.

Nowhere is this principle more apparent than in Lee’s land policies. Countless patriarchs’ plans for their property holdings have been dashed by Lee’s all-powerful land acquisition laws—freehold leases be damned. Countless others, who would have undoubtedly preferred their final resting places to be exactly that, have been dug up from their graves when the state decided their cemetery plots were needed for other purposes. If everyone else’s voice from the grave can be vetoed by the government, it’s not clear why Lee Kuan Yew’s should be the exception—especially when the government’s hardnosed, unsentimental approach to such matters is utterly in Lee’s own image.

By Singapore standards, therefore, it’s not necessarily sacrilegious for the government to consider the option of conserving Lee’s storied bungalow, no matter how firmly Lee would have opposed the idea. Part of the challenge of maturing our polity is to get used to the idea of operating by the rule of law, not the rule of Lee.

But maturation also demands that we pay close attention to the reasons Lee gave when he said, repeatedly, that he wanted his house flattened. This was in line with his well-known abhorrence of emotional pulls in politics, whether in the form of race, religion, language or charismatic personality. He wanted to build legitimacy around performance not identity, and to train Singaporeans to exercise a more clinical, legal-bureaucratic rationality.

You don’t need to be a disciple of Lee Kuan Yew to recognise this as a worthy principle for Singapore governance. Nor do you have to be a traitor to Lee Hsien Loong to acknowledge the risk, red-flagged by his siblings, that this principle will be compromised by preserving their house as a monument, against their father’s wishes.

Lee Wei Ling and Lee Hsien Yang fear that such a plan is being hatched to carry forward the family name to benefit the future political career of Lee Hsien Loong’s son. The prime minister and his wife have absolutely denied having any such dynastic ambitions.

The dynasty factor aside, though, we should remain wary of encouraging a political culture obsessed with personality. A people who are taught to credit their nation’s past progress to Great Men will long for more Great Men to solve future problems. That way lies the kind of populism and demagoguery that is rampant in today’s world.

The government should treat these concerns seriously if it’s contemplating overriding Lee Kuan Yew’s wishes. Even if the two younger Lee siblings’ most pointed allegations are unfounded, their broader concern is legitimate. The public interest should be insulated from the political interests of any individual or group.

The government would lose nothing but short-term pride if it were to dissolve its ministerial committee immediately and provide the assurance that any new body tasked to make recommendations will be constituted only after Lee Hsien Loong has left Cabinet. It serves nobody to allow any perception to linger that a government decision on the house is being influenced by Lee Hsien Loong’s private interest in capitalising on his father’s name.

The conflict of interest question can also be addressed by ensuring that any such committee is chaired by an independent eminent historian, and not by a politician or civil servant. It should be obliged to consult widely, especially with the Heritage Society and other relevant groups.

But it’s impossible to prevent a third or fourth generation Lee from milking an LKY monument for personal advantage down the line. Citizens of sound mind have a right to stand for election, and it is hard to think of a reasonable way to stop any candidate from talking about his or her family heritage.

In the first place, though, I wonder if we’re getting carried away with the fate of the house. Yes, 38 Oxley Road is an iconic site. But we need a sense of proportion. It is not what Jerusalem is to People of the Book. Nor is it Mount Doom in The Lord of the Rings—the place where the One Ring was forged, the only place it can be destroyed, and where the entire fate of Middle Earth hangs in balance.

No, the Lee family home is neither a necessary nor a sufficient possession for anyone determined to use or abuse the power of Lee Kuan Yew’s memory for selfish reasons. Even if it’s demolished, a replica could be erected elsewhere (including in Gardens by the Bay, still my choice of site that should be named after LKY). Alternatively, an augmented reality version could be reconstructed digitally, allowing people to put on a 3D headset for an immersive experience that, with the right music and narration, could be even more emotive—and manipulative—than a real-life visit to the actual site.

What’s more, since the vast majority of Singaporeans have no idea what the house looks like, a proposed monument doesn’t even need any connection to that address. For that matter, it doesn’t need to be a building. Even if the younger Lee siblings succeed in their bid to demolish No. 38, it’s not going to stop any individual or group from memorialising the LKY name through educational resources, books, movies, cartoons, songs, plays, paintings, exhibitions, t-shirts, stickers and other paraphernalia. The Estate could attempt to block commercially exploitative uses of the Lee name and likeness, but efforts to keep Brand LKY out of politics will probably be futile.

Indeed, the painful truth for the younger Lees is that the ship has probably already sailed. It weighed anchor at Lee Kuan Yew’s funeral, when most Singaporeans were moved by the sight of Lee Hsien Loong having to bear his Prime Ministerial duty to lead a mourning nation through its loss while at the same time dealing with his own grief as a son. In coldly political terms, this was the moment that being the son of LKY became a clear asset instead of a potential liability. A few months later, during the 2015 general election campaign, Lee Hsien Loong went so far as to channel his father in his Fullerton rally speech—“This is not a game of cards! This is your life and mine!” PAP critics may have been unimpressed, but to the party faithful, it was a goosebump-worthy moment.

All in all, it is simply unrealistic to try to stop anyone—least of all any member of the Lee family—from feeding an LKY cult, either deliberately or inadvertently. Instead, the more effective counter-strategy would be to build up Singaporeans’ critical thinking skills so we can resist simplistic Great Man accounts of history.

The core of this effort must be led by academic historians, who are best placed to help us develop a more contextual understand of our heritage, fed by multiple and even competing narratives. Also able to help develop society’s antibodies against demagoguery are filmmakers, playwrights and artists who, through their factual and fictional stories, have been trying to surface Singaporean narratives neglected by mainstream history. Sadly, some of the most thought-provoking creations in this genre—like Tan Pin Pin’s To Singapore, With Love and Sonny Liew’s The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye—have been treated as dissident works instead of the loving, nation-building reflections they really are. We should let historical discussions and debates flow, unimpeded by OB markers or censorship.

A more mature attitude to our history and politics can allow us to have the best of both worlds. We can honour and, yes, even monumentalise what is truly remarkable about our first Prime Minister, while avoiding the trap of deifying any mortal leader. Whether or not Lee Kuan Yew’s house remains standing isn’t really the issue. It’s whether we keep the doors and windows open to the fresh air of new information and ideas about our past and future.

– Photo of 38 Oxley Road: GOOGLE STREETVIEW

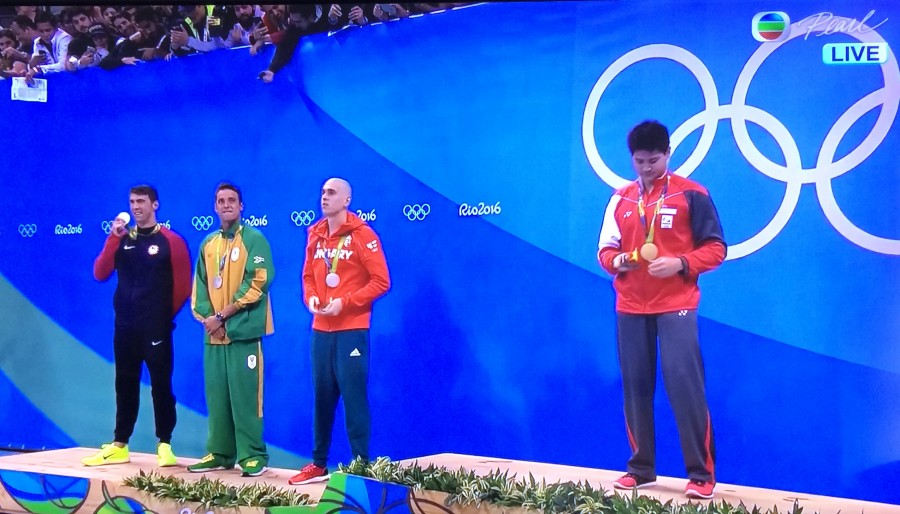

Many Singaporeans want Joseph Schooling exempted from National Service. Can the government bend the rules?

In the wake of Joseph Schooling’s spectacular, surging success in Rio de Janeiro, two-thirds of people I polled said that the young hero should now be excused from his National Service obligation. The inconvenient question of his NS status had been raised by a couple of friends, so I was curious to find out what others thought.

Admittedly, this was an unscientific survey, probably skewed by post-Rio euphoria, tilted toward the viewpoints of those with time to dawdle over social media, and under-representing men and women in uniform who are too busy keeping the country safe to take part in an online poll.

Nevertheless, I’d wager that most Singaporeans do indeed feel that Schooling should be allowed to continue serving the nation in his swimming trunks instead of a No. 4 camouflage uniform.

Those who don’t know Singapore may think that this reflects people’s indifference toward NS. I doubt that that’s the case. Singaporeans may complain about specific aspects of NS, but there is broad and deep commitment to the institution of compulsory enlistment for all males. NS is regarded as a key rite of passage, and one of the great equalisers in a divided society.

So, when Singaporeans say they are prepared to make an exception for Schooling, you can bet it’s not because they dismiss NS as no big deal, but because they regard his accomplishment as, well, Olympian.

This sentiment may put the Singapore government in a bind. With good reason, the government does not exempt able-bodied males from NS. Every now and then, Singaporeans suggest alternative avenues for service, including through sport. But the government has, correctly in my view, resisted calls to dilute the core mission of NS. It maintains that NS is meant to serve one purpose: defending the security of the nation. You can’t substitute it with other forms of contribution, no matter how valuable they may seem.

To do so would lead to endless bickering over legitimate justifications for being excused from military service. Take, for example, a young technopreneur who has just launched a world-beating startup that could be the next Samsung or Apple. Without the two-year interruption of NS, he could create a homegrown private-sector MNC—something as rare an Olympic medal, and much more tangible in value.

On what basis would this geek get his NS call-up while Schooling is allowed to continue chasing sporting glory?

The main reason I’m opposed to liberalising enlistment rules is that educated, upper middle class families are bound to benefit disproportionately—they are the ones who will be able to find the loopholes and write up convincing justifications. We could end up with a situation where less privileged Singaporeans are the ones compelled to put their lives on the line for the country.

I would not fault the government for thinking through such complications. After all, Singapore did not get to where it is through impulsive, arbitrary decision-making (except, perhaps, when dealing with critics and opponents). Bureaucratic rationality can be a massive turn-off, but with something like NS, the government really has no choice but to take into account boring things like rules and precedents.

And yet.

When we saw that gold medal around a Bedok boy’s neck; when we gaped at our Singapore flag flying higher than the American stars and stripes; when Majulah Singapura played, and we realised that hundreds of millions of people around the world might be listening with us—can anyone fault us for wanting even more?

What makes Schooling’s triumph in the 100m butterfly so addictively sweet is the sense that this is just the beginning. The 21-year-old can keep delivering, and if he is allowed time to sustain and better his world-beating performance, other Singaporeans will follow. This dream is not some mythical unicorn that vanishes into the night, but an achievable goal with the proven nation-building potential of competitive sport.

Schooling’s NS status is a policy dilemma that is emblematic of the times. On many fronts, Singapore’s leaders are called on to balance the hard truths that dictated past decisions with the less tangible needs of a First World society. If they are up to the challenge, they will be able to find a creative way to let Schooling keep swimming, without compromising the principle of universal conscription that underlies national defence.

Then, to quote another champ, Singapore can float like a butterfly and still sting like a bee.

A leader who is dismantling Indian secularism visits a nation built on its legacy.

The PAP’s stunning election victory doesn’t mean its remaking is complete.

Unlike-Lee admirers around the world may be missing significant details.

In an amusing case of mistaken identity, a banner honouring Lee Kuan Yew has appeared in India, bearing a photo of another Singaporean elder statesman, President Tony Tan. Both are white-haired ethnic Chinese males, but Tan, as you have may noted from Channel NewsAsia’s coverage of Lee’s funeral today, is rather more alive.

The picture has been making the rounds on social media in Singapore, bringing smiles to an otherwise sombre day. It serves as a useful reality check for Singaporeans, that although Lee has been lauded by world leaders as a 20th century giant, not everyone can recognise him from Tom, Dick or Tony.

Some other cases of mistaken identity are less trivial. It’s nothing new. For at least a couple of decades, he has been all things to all men who aspire to a certain kind of leadership. They see in him a model, a kind of proof-of-concept that they can point to when defending their own missions and methods. Leader X is Country A’s Lee Kuan Yew. How often have you heard that line.

As a Singaporean born in the year of the republic’s independence, I’ve benefited from Lee’s global brand, most tangibly in the fact that my red passport travels extremely well. But the way that brand is sometimes used is cringeworthy.

Most of the parallels that foreign politicians and their acolytes draw with Lee Kuan Yew are selective and self-serving. His name is evoked by anyone who wants to apply less-than-democratic means in the name of strong, decisive leadership in order to achieve high economic growth. But there was a lot more to the man and his formula for success.

The most obvious was the zero tolerance of corruption that he embodied and instituted in the Singapore system. That is probably a chapter in his bestselling memoirs that admirers like former Thai prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra skipped. Similarly, fans of Indonesia’s late president Suharto who cite his friendship with Lee conveniently ignore the fact that Suharto topped the world league table of corrupt leaders, according to the same organisation that routinely names Singapore as the cleanest in Asia.

Less noticed is the fact that Lee, while loudly dismissive of the liberal brand of democracy, never deviated from electoral authoritarianism – the belief that regular multi-party elections are ultimately the only way for a government to win legitimacy, and are not bad at keeping a dominant party on its toes. Of course, he did his best to insulate his government from distractions like short-term public opinion, an adversarial press and protest movements; he also treated the opposition unfairly, to put it mildly.

But, to this day, elections in Singapore remain competitive enough and credible enough to make democracy “the only game in town”, as political scientists would put it. As a result, opponents of the regime plot election strategy, not extra-parliamentary struggle; and Singaporeans accept the government’s authority as legitimate, even if they disagree with its policies. The thousands of Chinese officials who pass through Singapore to learn the Lee model may think this lesson can’t apply to the People’s Republic, but shouldn’t overlook how important it has been to Singapore’s success.

Back to India. When its government decided to fly the tricolour at half-mast today, I wonder which Lee they were honouring. I hope – but I doubt – that it was the leader who stood resolutely against sectarian politics and majority domination. Among all his core principles, this is the one least talked about abroad. Yet, to minorities like me – and, thankfully, most members of the majority race as well – this may be the single most precious aspect of the legacy.

Not that he got everything right. Older Indian Singaporeans still bristle at the way he labelled us as “fractious and contentious”. The stereotype might not have been off the mark (note Amartya Sen’s Argumentative Indian thesis), but if only he had seen it as a positive contribution to Singapore’s national culture rather than a weakness. Similarly, his open suspicion of Muslim Singaporeans’ growing religiosity was hurtful. Some of such straight-talking about race and religion could come back to haunt Singapore, should future bigots exploit his words to justify their prejudices.

But minorities never needed to doubt this: Lee was an unshakeable bulwark against majoritarian tendencies that could have easily overwhelmed Singapore. Malay/Muslims make up only 15% and Indians 7% of the population. For decades, the risk of a Chinese chauvinist party playing the race/language card posed the single biggest threat to PAP dominance. This fact is lost on most of the Western press, who self-aggrandisingly like to believe that they were Lee’s bête noire. They were more like sparring partners, compared with champions of the Chinese-speaking ground, who were the main victims of both detentions without trial as well as flagrant censorship.

Lee went to the extent of amending the republic’s Constitution to stop any party from sweeping into power without minority support. For most Parliamentary seats, candidates are forced to contest as small teams that must include minorities. Thus, no Chinese party could do in Singapore what the BJP did in India last year – come to power without a single MP from the country’s largest minority group.

Thankfully, Lee and his comrades were influenced by an older Indian tradition, the Nehruvian secular ideal that accommodated minorities – the same tradition that the BJP and the larger Hindutva movement is bent on dismantling.

Singapore should not presume that it can serve as a model for any other country, least of all India. The world’s largest democracy is 200 times larger than the city state that Lee ran, and its challenges are profoundly more complex.

But if foreigners do choose to honour Lee Kuan Yew, they shouldn’t fall into the mistaken-identity trap. Yes, he was a firm leader who stretched the limits of democratic government to breaking point in order to get things done.

But a leader who makes minorities feel unwanted, insecure and fearful?

That’s not a face that Singaporeans recognise.

Looking beyond the liberal/conservative divide

Some will see it as a victory for a vocal minority of liberals. Others will declare it a conservative triumph. Perhaps, though, it was never about where the government landed on the left-right spectrum. What was really at stake were the principles by which a multi-cultural nation makes decisions that will inevitably offend one community or another.

This specific controversy was over three children’s books meant to teach kids about non-conventional families. The National Library Board’s professional librarians had earlier decided they were suitable for acquisition, but some parents complained that the books were too soft on homosexuality. As a result, the books were to be discarded. Following a public outcry, the government intervened, in time to save two books from pulping. They will not be returned to the children’s shelves, but will be made available in the adult section.

Compared with the earlier decision, this is a passable compromise. It concedes to the conservatives that the books should not be freely available to all children regardless of the moral objections of some of their parents. At the same time, it does not permit these parents to dictate standards for all library users: adults interested in teaching their own children to be more broad-minded about what constitutes a loving family can still borrow the books.

What was striking about the earlier decision was not so much that it did not conform to liberal standards (nothing new there), but that it deviated from the government’s own principles. For more than 20 years, it has been official policy to avoid censorship when classification would do. A totally laissez faire approach to public morals would fall short of the fundamental societal obligation to protect the young; it would risk treating children like adults. At the other extreme, a crude censorship approach treats adults like children, denying them choices that they are entitled to.

In contrast, classification maximises choice for consenting adults while protecting the vulnerable. NLB’s original response to the conservatives’ complaints was inconsistent with this rational, well-established approach. The latest decision simply brings the practice more in line with the principle. Instituting a proper, transparent review process would have to be the next step. Expert judgments by professional librarians need to be shielded from shadowy complainants who are not prepared to come out to justify their positions publicly.

Even more disquieting was the fact that the decision to pulp was part of a wider pattern, of deciding cultural policy based on how offended people are. It is dangerous for the government of a multi-ethnic country to resolve disputes this way, even if they side with the majority. Once the referee signals that he will side with those who cry the loudest, some players will start outperforming the most talented World Cup actors.

In football, at least, an eagle-eyed referee and slow-motion HD replays can discover the truth: was it a real foul or did he dive? When it comes to religion and morality, however, it is all subjective. No amount of rational theological forensics can establish whether a believer’s outrage is justified. Governments that agree to play this game end up having to take community leaders’ word for it, that they are suffering intolerable indignity.

Around the world, religious leaders use this inherent uncertainty to their own political advantage. Claiming to be offended and then declaring battle against the real or imagined source of that offence is one of the easiest ways to galvanise your followers; gain a higher profile than your competitors; put opponents on the defensive; and play the state like a puppet. It happens in Malaysia; it can happen here.

Indeed, as the most religiously diverse country in the world, Singapore is particularly prone to this risk. There is no limit to the offence that the intolerant can choose to take from what other communities do. Proselytisation by Christians and polygamy among Muslims are just two examples of practices that some consider consistent with their faiths – but that others find upsetting. Thus, restrictions based on the capacity to offend won’t just hurt secular liberals; it will also backfire on the most devout.

In most countries, like Malaysia, the state simply sides with the majority community (it’s wrong, but at least it’s unambiguous). Here, where there is no religious majority, the state will find itself pushed this way and that. And the ultimate result will be the conclusive unwinding of Singaporean experiment in multi-racial, multi-religious harmony.

The only responsible approach for a society like Singapore is for the state to adopt a strong bias for tolerance, and suppress nothing other than the most extreme of speech. Adult Singaporeans need to be educated to look after their own feelings.

After decades of enjoying the dubious privilege of turning to a nanny state whenever one feels offended, many Singaporeans will find this a difficult adjustment. Indeed, by changing tack, the government may lose more votes than it wins. But it is the only viable strategy for a crowded city-state whose greatest asset, as well as its greatest challenge, will always be its cultural diversity.

Let’s stop judging activism in PAP-centric terms

Last month, thousands gathered at the floating stage in Marina Bay for Singapore’s observance of Earth Hour, dubbed the world’s largest mass participation event ever. An offshoot of the nature conservation group WWF, Earth Hour is now headquartered in Singapore, thanks in part to government incentives to turn the country into a hub for international nonprofits. The event was graced by a senior Singapore diplomat and supported by the private sector, including media outlets drawn by the star power of the Amazing Spider-Man cast.

The same month, a group called Maruah marked the International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination and International Women’s Day with important statements on how Singapore could make further improvements in addressing inequality. Maruah is Singapore’s human rights NGO. Its causes are not populist. As if it was not difficult enough for Maruah’s campaigns to gain public acceptance, the government has placed extra hurdles before it. Its fundraising is restricted under the Political Donations Act, and it recently had trouble booking even a dosai restaurant for an event, let alone the iconic Float@Marina.

Earth Hour and Maruah represent two faces of activism in Singapore. The people behind them are passionately devoted to making the world better by pushing for changes in values that will ultimately translate into more enlightened policy. But official receptivity towards them could not be more different.

Of course, even liberal democracies do not treat all kinds of activism equally. At one end of the spectrum are causes that enjoy state support. A government may actively facilitate citizen initiatives aligned with its own agenda (e.g. the Canadian government provides subsidies for events promoting intercultural and interfaith understanding, as part of its multiculturalism mission).

At the other extreme, democracies prohibit certain methods of activism. Activists who literally throw stones, destroy property or hack into websites face arrest, no matter how noble their causes. It is also reasonable for authorities to impose restrictions on where, when and how boisterous demonstrations can be conducted. Sometimes, activists’ goals are seen as incompatible with protecting others’ dignity and basic rights and dignity (e.g. Germany bans National Socialism because of its genocidal track record).

Then, there is the large in-between category of activism that is neither positively supported by the state nor treated as illegal. It faces the mixed blessing of benign neglect: the lack of official support means that this zone is often the most creative and innovative.

Singapore approach

Activism in Singapore deviates from these democratic norms in two respects. First, some activism is treated as illegal even though it poses no threat to public order and does not violate the rights of other citizens. One example of this is the banning of video interviews of former detainees, produced in order to present their versions of the Singapore story. The only interest served by such legal action is to protect the government’s ideological control, which is not a legitimate reason for censorship in a democratic society.

Second, the large middle category of merely tolerated activism – permitted but not supported – is further subdivided, with some forced to face more official restrictions and obstacles than others. Unwanted special treatment could come in the form of extra layers of regulation, difficulties in securing venues for events, and blacklisting of volunteers when they apply for public sector jobs.

Such discrimination might be acceptable if the targets were bona fide threats to national security. Often, however, they are at worst inconvenient to government, forcing officials to spend more time and effort defending their policies. Official hypersensitivity to dissent was illustrated recently by remarks made by a senior civil servant to the Straits Times. Warning that policy-making should not be hijacked by what he described by “a very loud and noisy minority”, he cited the example of the campaign against the death penalty. These activists were certainly passionate and outspoken, but they barely registered on the political decibel scale. They could seem “loud and noisy” only to ears quite unaccustomed to hearing dissonant voices.

Where the government draws the line between permitted and restricted activity can be inconsistent. Take its oft-stated position that Singapore politics is a matter for Singaporeans, and that groups that may influence public affairs should be banned from receiving foreign funding. This argument has been used to restrict the growth of Maruah as well as citizen media like The Online Citizen and the Independent. It is also used to prevent some event organisers from bringing in foreign speakers.

Yet, there are much larger and more influential organisations that face no such restrictions. Certain religious groups, for example, have made their presence felt in national debates on contentious issues such as sexuality. The rise of intolerant brands of Christianity and Islam in Singapore can be traced to material and doctrinal support from the United States and Saudi Arabia respectively. Similarly, our cultural and entertainment spaces have given virtually free rein to foreign influences, in ways that have spread consumerist values and the objectification of women. Thus, powerful right-wing religious as well as commercial forces have been allowed untrammeled access to the public mind, while tiny groups of Singaporeans who want to counter these trends by advocating secular, non-commercial, human-rights values face official obstruction. Such discrimination happens because of the arbitrary manner in which some activities are labeled “political”, bearing little relation to what actually does affect political values.

Discriminatory treatment of activists is shored up with highly subjective language. For example, citizen participation is encouraged – but it should not get “political”. We are routinely told that Singapore welcomes criticism – as long as it is “constructive”. We want ideas that are out of the box – but not “adversarial”. Singaporeans should serve with passion, but without “agendas”. And so on. Such distinctions are in the eyes of the beholder, and in Singapore the only beholder that counts is the government.

Singaporeans have internalised these ideological categories. Critics deploy the same language to plead that their own comments should not be mistaken as destructive or adversarial. For example, after the website Breakfast Network chose to shut down rather than comply with the government’s new registration requirements, its founder objected to a report stating that it “refused” to register, saying that “declined” was a better word because “refused… makes us sound like rebels”. Similarly, civil society groups bend over backwards to avoid the accusation that they are “political”. Such sensitivity to semantics is a learnt response to the government’s “OB” markers, but it also legitimises and perpetuates those same divisions.

Activists at the other end of the political spectrum can be equally susceptible to these mental divides. They display a kind of reverse snobbery, pooh-poohing activists who are not as anti-government as they are. No doubt, certain causes require more political courage than others – with, say, disability rights lying at the less politically-contentious end of the spectrum, civil and political rights at the opposite extreme, and nature and heritage conservation somewhere in the middle. Surely, however, the respect that we show one another within civil society should depend on one’s sincerity, knowledge, wisdom, selflessness and hard work; I am not sure why being anti-government should be the only badge of honour.

Anti-ISA event at Hong Lim Park.

Like its critics, the government should stop judging activism in PAP-centric terms. Yes, activism needs to be regulated. But, the test should not be how much a cause deviates from official positions. Yes, government should protect public order and the rights of others. But, there is no need to protect Singaporeans – least of all public servants – from discomfiting ideas.

We are about to celebrate 50 years as an independent, citizen-governed state; recently, we have been congratulating ourselves on the quality of an education system that is producing young people who are apparently world beaters in problem-solving and coping with complexity. Policies that do not trust citizens to make their own judgments about which activists to side with make a mockery of these milestones.

– This article was prepared for a panel discussion, “The Turning Tide: The State of Activism in Singapore”, held on 17 May 2014 at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, NUS, as part of its Angsana Evening series.

Page 1 of 3

Powered by WordPress & Theme by Anders Norén