A SELFISH & IRRESPONSIBLE RIGHT?

Singapore Advocacy Awards Lecture, 4 July 2015.

Unlike-Lee admirers around the world may be missing significant details.

In an amusing case of mistaken identity, a banner honouring Lee Kuan Yew has appeared in India, bearing a photo of another Singaporean elder statesman, President Tony Tan. Both are white-haired ethnic Chinese males, but Tan, as you have may noted from Channel NewsAsia’s coverage of Lee’s funeral today, is rather more alive.

The picture has been making the rounds on social media in Singapore, bringing smiles to an otherwise sombre day. It serves as a useful reality check for Singaporeans, that although Lee has been lauded by world leaders as a 20th century giant, not everyone can recognise him from Tom, Dick or Tony.

Some other cases of mistaken identity are less trivial. It’s nothing new. For at least a couple of decades, he has been all things to all men who aspire to a certain kind of leadership. They see in him a model, a kind of proof-of-concept that they can point to when defending their own missions and methods. Leader X is Country A’s Lee Kuan Yew. How often have you heard that line.

As a Singaporean born in the year of the republic’s independence, I’ve benefited from Lee’s global brand, most tangibly in the fact that my red passport travels extremely well. But the way that brand is sometimes used is cringeworthy.

Most of the parallels that foreign politicians and their acolytes draw with Lee Kuan Yew are selective and self-serving. His name is evoked by anyone who wants to apply less-than-democratic means in the name of strong, decisive leadership in order to achieve high economic growth. But there was a lot more to the man and his formula for success.

The most obvious was the zero tolerance of corruption that he embodied and instituted in the Singapore system. That is probably a chapter in his bestselling memoirs that admirers like former Thai prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra skipped. Similarly, fans of Indonesia’s late president Suharto who cite his friendship with Lee conveniently ignore the fact that Suharto topped the world league table of corrupt leaders, according to the same organisation that routinely names Singapore as the cleanest in Asia.

Less noticed is the fact that Lee, while loudly dismissive of the liberal brand of democracy, never deviated from electoral authoritarianism – the belief that regular multi-party elections are ultimately the only way for a government to win legitimacy, and are not bad at keeping a dominant party on its toes. Of course, he did his best to insulate his government from distractions like short-term public opinion, an adversarial press and protest movements; he also treated the opposition unfairly, to put it mildly.

But, to this day, elections in Singapore remain competitive enough and credible enough to make democracy “the only game in town”, as political scientists would put it. As a result, opponents of the regime plot election strategy, not extra-parliamentary struggle; and Singaporeans accept the government’s authority as legitimate, even if they disagree with its policies. The thousands of Chinese officials who pass through Singapore to learn the Lee model may think this lesson can’t apply to the People’s Republic, but shouldn’t overlook how important it has been to Singapore’s success.

Back to India. When its government decided to fly the tricolour at half-mast today, I wonder which Lee they were honouring. I hope – but I doubt – that it was the leader who stood resolutely against sectarian politics and majority domination. Among all his core principles, this is the one least talked about abroad. Yet, to minorities like me – and, thankfully, most members of the majority race as well – this may be the single most precious aspect of the legacy.

Not that he got everything right. Older Indian Singaporeans still bristle at the way he labelled us as “fractious and contentious”. The stereotype might not have been off the mark (note Amartya Sen’s Argumentative Indian thesis), but if only he had seen it as a positive contribution to Singapore’s national culture rather than a weakness. Similarly, his open suspicion of Muslim Singaporeans’ growing religiosity was hurtful. Some of such straight-talking about race and religion could come back to haunt Singapore, should future bigots exploit his words to justify their prejudices.

But minorities never needed to doubt this: Lee was an unshakeable bulwark against majoritarian tendencies that could have easily overwhelmed Singapore. Malay/Muslims make up only 15% and Indians 7% of the population. For decades, the risk of a Chinese chauvinist party playing the race/language card posed the single biggest threat to PAP dominance. This fact is lost on most of the Western press, who self-aggrandisingly like to believe that they were Lee’s bête noire. They were more like sparring partners, compared with champions of the Chinese-speaking ground, who were the main victims of both detentions without trial as well as flagrant censorship.

Lee went to the extent of amending the republic’s Constitution to stop any party from sweeping into power without minority support. For most Parliamentary seats, candidates are forced to contest as small teams that must include minorities. Thus, no Chinese party could do in Singapore what the BJP did in India last year – come to power without a single MP from the country’s largest minority group.

Thankfully, Lee and his comrades were influenced by an older Indian tradition, the Nehruvian secular ideal that accommodated minorities – the same tradition that the BJP and the larger Hindutva movement is bent on dismantling.

Singapore should not presume that it can serve as a model for any other country, least of all India. The world’s largest democracy is 200 times larger than the city state that Lee ran, and its challenges are profoundly more complex.

But if foreigners do choose to honour Lee Kuan Yew, they shouldn’t fall into the mistaken-identity trap. Yes, he was a firm leader who stretched the limits of democratic government to breaking point in order to get things done.

But a leader who makes minorities feel unwanted, insecure and fearful?

That’s not a face that Singaporeans recognise.

Let’s stop judging activism in PAP-centric terms

Last month, thousands gathered at the floating stage in Marina Bay for Singapore’s observance of Earth Hour, dubbed the world’s largest mass participation event ever. An offshoot of the nature conservation group WWF, Earth Hour is now headquartered in Singapore, thanks in part to government incentives to turn the country into a hub for international nonprofits. The event was graced by a senior Singapore diplomat and supported by the private sector, including media outlets drawn by the star power of the Amazing Spider-Man cast.

The same month, a group called Maruah marked the International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination and International Women’s Day with important statements on how Singapore could make further improvements in addressing inequality. Maruah is Singapore’s human rights NGO. Its causes are not populist. As if it was not difficult enough for Maruah’s campaigns to gain public acceptance, the government has placed extra hurdles before it. Its fundraising is restricted under the Political Donations Act, and it recently had trouble booking even a dosai restaurant for an event, let alone the iconic Float@Marina.

Earth Hour and Maruah represent two faces of activism in Singapore. The people behind them are passionately devoted to making the world better by pushing for changes in values that will ultimately translate into more enlightened policy. But official receptivity towards them could not be more different.

Of course, even liberal democracies do not treat all kinds of activism equally. At one end of the spectrum are causes that enjoy state support. A government may actively facilitate citizen initiatives aligned with its own agenda (e.g. the Canadian government provides subsidies for events promoting intercultural and interfaith understanding, as part of its multiculturalism mission).

At the other extreme, democracies prohibit certain methods of activism. Activists who literally throw stones, destroy property or hack into websites face arrest, no matter how noble their causes. It is also reasonable for authorities to impose restrictions on where, when and how boisterous demonstrations can be conducted. Sometimes, activists’ goals are seen as incompatible with protecting others’ dignity and basic rights and dignity (e.g. Germany bans National Socialism because of its genocidal track record).

Then, there is the large in-between category of activism that is neither positively supported by the state nor treated as illegal. It faces the mixed blessing of benign neglect: the lack of official support means that this zone is often the most creative and innovative.

Singapore approach

Activism in Singapore deviates from these democratic norms in two respects. First, some activism is treated as illegal even though it poses no threat to public order and does not violate the rights of other citizens. One example of this is the banning of video interviews of former detainees, produced in order to present their versions of the Singapore story. The only interest served by such legal action is to protect the government’s ideological control, which is not a legitimate reason for censorship in a democratic society.

Second, the large middle category of merely tolerated activism – permitted but not supported – is further subdivided, with some forced to face more official restrictions and obstacles than others. Unwanted special treatment could come in the form of extra layers of regulation, difficulties in securing venues for events, and blacklisting of volunteers when they apply for public sector jobs.

Such discrimination might be acceptable if the targets were bona fide threats to national security. Often, however, they are at worst inconvenient to government, forcing officials to spend more time and effort defending their policies. Official hypersensitivity to dissent was illustrated recently by remarks made by a senior civil servant to the Straits Times. Warning that policy-making should not be hijacked by what he described by “a very loud and noisy minority”, he cited the example of the campaign against the death penalty. These activists were certainly passionate and outspoken, but they barely registered on the political decibel scale. They could seem “loud and noisy” only to ears quite unaccustomed to hearing dissonant voices.

Where the government draws the line between permitted and restricted activity can be inconsistent. Take its oft-stated position that Singapore politics is a matter for Singaporeans, and that groups that may influence public affairs should be banned from receiving foreign funding. This argument has been used to restrict the growth of Maruah as well as citizen media like The Online Citizen and the Independent. It is also used to prevent some event organisers from bringing in foreign speakers.

Yet, there are much larger and more influential organisations that face no such restrictions. Certain religious groups, for example, have made their presence felt in national debates on contentious issues such as sexuality. The rise of intolerant brands of Christianity and Islam in Singapore can be traced to material and doctrinal support from the United States and Saudi Arabia respectively. Similarly, our cultural and entertainment spaces have given virtually free rein to foreign influences, in ways that have spread consumerist values and the objectification of women. Thus, powerful right-wing religious as well as commercial forces have been allowed untrammeled access to the public mind, while tiny groups of Singaporeans who want to counter these trends by advocating secular, non-commercial, human-rights values face official obstruction. Such discrimination happens because of the arbitrary manner in which some activities are labeled “political”, bearing little relation to what actually does affect political values.

Discriminatory treatment of activists is shored up with highly subjective language. For example, citizen participation is encouraged – but it should not get “political”. We are routinely told that Singapore welcomes criticism – as long as it is “constructive”. We want ideas that are out of the box – but not “adversarial”. Singaporeans should serve with passion, but without “agendas”. And so on. Such distinctions are in the eyes of the beholder, and in Singapore the only beholder that counts is the government.

Singaporeans have internalised these ideological categories. Critics deploy the same language to plead that their own comments should not be mistaken as destructive or adversarial. For example, after the website Breakfast Network chose to shut down rather than comply with the government’s new registration requirements, its founder objected to a report stating that it “refused” to register, saying that “declined” was a better word because “refused… makes us sound like rebels”. Similarly, civil society groups bend over backwards to avoid the accusation that they are “political”. Such sensitivity to semantics is a learnt response to the government’s “OB” markers, but it also legitimises and perpetuates those same divisions.

Activists at the other end of the political spectrum can be equally susceptible to these mental divides. They display a kind of reverse snobbery, pooh-poohing activists who are not as anti-government as they are. No doubt, certain causes require more political courage than others – with, say, disability rights lying at the less politically-contentious end of the spectrum, civil and political rights at the opposite extreme, and nature and heritage conservation somewhere in the middle. Surely, however, the respect that we show one another within civil society should depend on one’s sincerity, knowledge, wisdom, selflessness and hard work; I am not sure why being anti-government should be the only badge of honour.

Anti-ISA event at Hong Lim Park.

Like its critics, the government should stop judging activism in PAP-centric terms. Yes, activism needs to be regulated. But, the test should not be how much a cause deviates from official positions. Yes, government should protect public order and the rights of others. But, there is no need to protect Singaporeans – least of all public servants – from discomfiting ideas.

We are about to celebrate 50 years as an independent, citizen-governed state; recently, we have been congratulating ourselves on the quality of an education system that is producing young people who are apparently world beaters in problem-solving and coping with complexity. Policies that do not trust citizens to make their own judgments about which activists to side with make a mockery of these milestones.

– This article was prepared for a panel discussion, “The Turning Tide: The State of Activism in Singapore”, held on 17 May 2014 at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, NUS, as part of its Angsana Evening series.

Not all worthy causes are vote-winners; that’s why politics shouldn’t be left to political parties.

August 28, the day that Vincent Wijeysingha announced his resignation from the Singapore Democratic Party to devote himself to the struggle for civil liberties, happened to mark the 50th anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have A Dream” speech, addressed to the largest civil rights demonstration in history. Whether this was pure happenstance, a conscious nod to history, or ordained by zodiacal forces – I have no idea. In any case, the coincidence does inspire reflection on the role of such activism in modern politics.

In normal countries, it is unremarkable to see individuals pass back and forth through the revolving door between electoral politics and civil society activism. Several politicians come from civil society in the first place and quite naturally return to their roots. Ralph Nader continues to work as a consumer rights and environmental activist in between US presidential bids. In Malaysia, many leading lights straddle party politics and civil society. Irene Fernandez, for example, is a council member of the opposition PKR, but is better known as a human rights defender and the head of advocacy group Tenaganita.

In Singapore, few politicians come from civil society, and the little traffic there is tends to be one-way. PAP ideology prefers political beings to go through a life cycle with distinct stages, culminating in elected office. It’s like metamorphosis. A caterpillar is allowed to transform into a butterfly, but while it’s just a caterpillar, it should know its place, keep its head down, and never act as if it has the right to flaunt its colours or to fly – that’s butterfly territory.

Over the decades, the government has reinforced this order by restricting societies’ establishment and operation. It also sticks on troublesome groups and individuals such labels as “political”, “agenda” and “partisan” (pap for short; you could say that big PAP is not fond of little pap’s), which basically means that they will be treated as akin to national security threats.

The logic of these labels is questionable: after all, any intervention in the public sphere is at some level “political”. And when does a passionate interest in issues (something that the government says it wants to encourage through initiatives like the proposed Youth Corps) become an “agenda” deserving of its proverbial knuckle-duster treatment? As for partisanship, not even a constitution that disallows it from affiliating itself with any political party was able to save the human rights group Maruah from being subject to the Political Donations Act, which was ostensibly meant to keep money out of the electoral system.

But so overpowering are these labels that most of their targets usually scramble to live them down, rather than trying to challenge the assumptions behind them. Most civil society groups tend to err on the side of caution rather than risk being called “political”. And the SDP took pains to stress that it did not have a gay “agenda”, whatever that means.

Twenty years ago, a bunch of political kaypohs (including this one) got together to form a group called the Roundtable. It challenged the government’s position that individuals with a political agenda should only work through political parties. We felt differently: that it was the right and responsibility of citizens to be engaged in our nation’s civic life, and that non-partisan engagement was both necessary and legitimate.

The Roundtable managed to get registered as a society and operated for a few years before it ran out of steam. It would be nice to believe that the group pushed back the “OB” markers, staking out a bit more space for civil society.

However, the ruling party’s ideology still has a strong hold. To see how deeply entrenched is the PAP’s life-cycle view of political participation – that individuals who are serious about their causes should come out from civil society, join political parties and not turn back – look no further than some of the comments that greeted Wijeysingha’s announcement. “If you want change, join a political party, rally people to your cause, get into Parliament – and change things,” went one.

Clearly, the significance of that day’s worldwide remembrance of Martin Luther King and the civil rights movement was lost on such commentators.

The simple reason why civil society activism is a vital complement to electoral politics in a democratic society is that not every worthy cause is a vote winner. Often, it takes time for the majority to get on board. Sometimes, they never do. Government leaders then have to decide whether to do the right thing even though most voters remain nonplussed or outright opposed to change.

In proportional-representation systems, parties can win seats despite championing minority causes. Green parties in Europe are a case in point. But in a first-past-the-post, winner-take-all electoral system like ours, it is unlikely that any political party will push issues supported by only a minority of voters. Invariably, civil society activism is needed to give governments a nudge.

As necessary as electoral democracy is for a country’s well-being, it is not sufficient. Consider some of the principles that today’s Singaporeans benefit from. The right of women to vote; or of Asians to govern their own societies. The moral unacceptability of putting children to work instead going to school; or of enslaving adults.

We now take these for granted as fairly basic requirements of a civilised society. Yet, these principles did not always enjoy such common-sense status. In an earlier time in many societies, even many victims who stood to benefit from enlarged rights and liberties did not consider their lot as an abomination but as the natural order of things. Changing people’s attitudes and lawmakers’ calculations took decades of consciousness-raising by activists, writers and other people of conscience who were focussed on winning the favour of history, not conforming with the flavour of the times.

Let’s not kid ourselves that we – in Singapore or anywhere else – have already achieved a state of civilisational perfection. Future generations will be contemptuous of some of today’s social mores and public policies, just as we look down on our forebears for practising or condoning what we in a more enlightened age know to be wrong. It would be hubris to expect otherwise. The only uncertainty is what exactly history will judge to be the greatest injustices of our time. For those who would like to know sooner than later, history shows that the clues are more likely to come from civil society than from political parties.

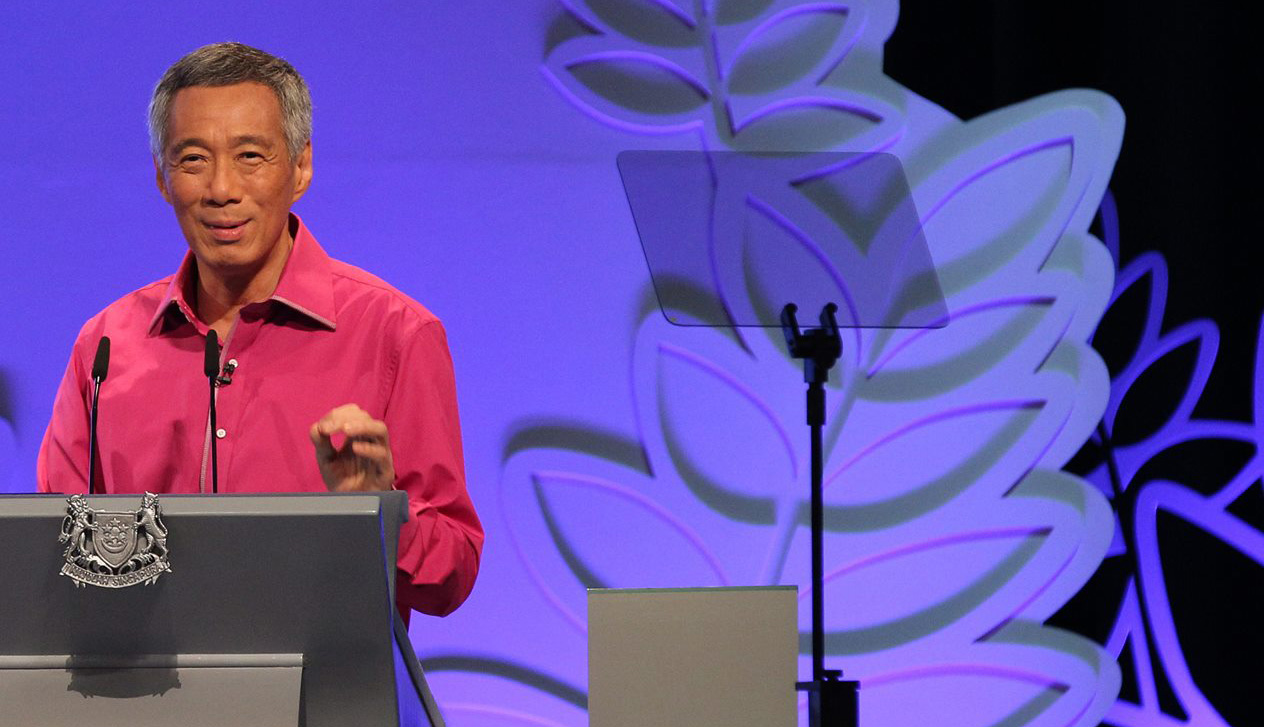

The Prime Minister’s National Day Rally Speech avoids political controversy.

This evening’s National Day Rally Speech was probably Lee Hsien Loong’s best ever, because he played to his government’s strengths – and sidestepped its main weakness.

Compared with most states, the PAP government has traditionally scored an A* in tinkering with policies to stay responsive to the needs of the majority. It has found it harder to excel in this subject lately, perhaps because the local population and the global economy have changed the syllabus. Nevertheless, the PM showcased the PAP’s technocratic talents, trying to tackle key concerns over housing, healthcare and schooling.

Importantly, he recognised that with trust in the PAP’s capacity to deliver at all-time low, a battery of acronyms old and new would not be enough to win the public over. Neither would it suffice to recite past accomplishments, for that would signal complacency on the PAP’s part. Instead, he punctuated the announcements with some simple and powerful words: “I promise,” he said at the start; and “Don’t worry” he declared more than once. These assurances might have fallen flat if they had come from some of his colleagues, but many Singaporeans, even among those who feel his government has lost its way, would concede that his own dedication to his job is hard to fault. When speaking about ordinary Singaporeans who overcame hardships, he had to fight back tears. It’s not the first time. Lee’s eyes may light up when he talks about cutting-edge technology, but they reveal the most emotion when he’s reminded of the lives that can be improved when grassroots grit and sensitive policies meet.

The second T-score-boosting skill of the PAP has been its breathtaking ability to dream big. And it hardly gets bigger than the plans for Changi Airport, Paya Lebar Air Base, the new port at Tuas and the old one at Tanjong Pagar. Of course, when full details are revealed, there will probably be plenty to quibble over. But, in contrast to countries where megaprojects are more discussed than delivered, I don’t think anyone doubts that this government will get the job done.

It was a smart choice to focus on these particular infrastructural projects in the Rally speech. Many Singaporeans are uneasy about their country becoming the region’s playground – which is what the integrated resorts are making it – but few question the ambition to remain Asia’s air and sea transport hub, which is a far deeper, existential part of Singapore’s identity.

If his speech goes down well, it will also be because he didn’t add to the mix the one thing that usually gets stuck in the craw. He made passing reference to the need to “get the politics right” – a line that has featured in most of his major speeches in recent years. But, this time, he’d clearly decided against elaborating on the point. He paid the opposition and other online critics the ultimate insult of ignoring them. Perhaps he decided that, since his government is not ready to cede any ideological ground, it is pointless to attract unnecessary attention to that fact. The PAP may also have arrived at the conclusion that some sections of the population just cannot be won over.

The question is whether the non-inclusion of political reform in the NDR agenda is a sign of things to come, or, rather, not to come. Some of us feel strongly that the Singapore project is incomplete as long as democratic institutions and practices remain underdeveloped. The PAP’s 2011 electoral setback seemed a timely moment to for the ruling party to reconsider its political blueprint. However, there was always going to be an alternative scenario: the PAP would bypass the need for structural political change and focus instead on correcting its social and economic policies to win back the middle ground. Economist and former civil servant Donald Low was among those who saw this as the most likely, though sub-optimal, of the PAP’s possible responses.

It is, after all, the only way it knows how to govern. Singaporeans’ age-old social compact with the PAP was “give me liberty or give me wealth” – as former Straits Times columnist and academic Russell Heng nailed it more than 20 years ago. Many argue that a new generation of Singaporeans cannot be so easily bought – or that this is no longer a tenable trade-off, since wealth creation in the new economy will depend increasingly on more freedom of thought and expression. However, it is an open question whether this theory that authoritarianism is unsustainable was ever anything other than wishful thinking on the part of liberals.

Judging by PM Lee’s speech, it certainly doesn’t look as if the PAP believes that its politics requires a new way forward.

The Punggol by-election reintroduced Singaporeans to laugh-a-minute opposition parties. The Workers’ Party is not one of them.

In the end, the three-way split in the opposition assault on Punggol East proved immaterial. The Workers’ Party has won the constituency with an outright, unambiguous majority.

This had seemed like the ruling party’s seat to lose. In the last General Election, it won the seat with 54.5 percent of the valid votes. That was barely 21 months ago. Since then, PAP may not have satisfied most Singaporeans that it has fully reformed itself or fixed everything that needs to be fixed, and policy improvements may not yet be felt on the ground – but few fair-minded Singaporeans could honestly claim that the PAP has actually become much worse since May 2012. That being the case, it wasn’t clear how the WP was going to pick up the additional votes it needed to swing the constituency.

Sure, the PAP incumbent let down his constituents. But, thanks to the leadership’s swift and decisive response, it did not seem likely that voters would blame the party for the wayward Palmer. Importantly, the PAP maintained its apologetic tone, fighting a gentlemanly campaign and dispensing with the scare tactics, unfair inducements and bully behaviour that has marred previous elections.

On the other side, the Workers’ Party appeared to lose some of its 2011 sheen. The single most significant development in the Punggol East by-election campaign was the boiling over of opposition antipathy towards the WP.

Opposition disunity is nothing new. But past opposition leaders tended to bite their tongues or confine themselves to the occasional thinly veiled snide remark. Kenneth Jeyaretnam’s criticism of the WP marked the first time in memory that the leader of a prominent opposition party launched a full-frontal assault on another.

The PAP took advantage of this windfall by echoing Jeyaretnam’s criticism: it agreed that the WP hadn’t really made a difference. This was an unusual line for a ruling party that has traditionally equated the growth of the opposition with the End Of Singapore As We Know It.

If the charge of WP impotence had been levelled by the Reform Party alone, or by the PAP alone, it would have been discounted by most voters as mere rhetoric. But to hear the same point from both ends of the political spectrum could have shaken the faith of some voters who have otherwise been inclined to vote for the WP.

How then did the WP pull it off? It is tempting to conclude that this was a protest vote, signalling voters’ rejection of the PAP’s efforts since May 2011. But this theory may not give enough credit to the WP’s tactical genius.

We now have enough evidence to conclude that Low Thia Khiang is Singapore’s best electoral strategist. The decision to re-field Lee Li Lian – instead of some new star catch or one of his more famous NCMPs – seemed anti-climactic at the time. In hindsight, I wonder how many decisive swing votes WP got by demonstrating to Punggol East voters that they could count on the WP for constancy and loyalty – a particularly powerful message in the wake of their betrayal by their former PAP MP.

The WP may also have been able to capitalise on the PAP’s understandable wavering, over whether to treat this like Koh Poh Koon’s fight or to roll out the big guns. The first approach could make the PAP look too weak, while the latter would make it look desperate. The WP had no such self-doubt. They consistently signalled to constituents that their entire party leadership was here for them. At each rally, the WP’s entire star cast was there on stage. For a constituency in the far north, unreached by the amenities enjoyed by more central and mature estates, such attention must have been novel and welcome.

However they did it, this is a result that no politician anywhere on the political spectrum can ignore. For the PAP, it is not really anything new. It already knew that it had to correct its course. It would do well to consider whether it has moved decisively enough since May 2011. But it can also comfort itself that it might already be doing the right thing, except that policies take time to bear fruit, so the people “don’t feel it yet”, as Bill Clinton said in his speech supporting Barack Obama.

What will certainly be felt tonight, though, are the shockwaves in the rest of the opposition. I doubt if two party leaders have ever does so disastrously in a Singapore election as Kenneth Jeyaretnam and Desmond Lim performed today. For them, there is nowhere to hide. They will search for others to blame, but should eventually accept reality.

The Workers’ Party had seemed stand-offish, even arrogant, in its dealings with the rest of the opposition in the run-up to this poll. It was like the WP was trying to say to everyone else in the opposition, we are different.

Guess what. They are.

Only six times before has the Opposition wrested a constituency from PAP hands. Lee Li Lian’s margin compares favourably with all the previous instances. It is similar to the margin in Aljunied GRC in 2011. Only Chiam See Tong, who took Potong Pasir with 60% in 1984, did better in a single seat ward.

If “Rejected Votes” were a candidate, it would have beaten both Kenneth Jeyaretnam and Desmond Lim. There were 415 rejected votes, compared with 353 and 168 votes for Jeyaretnam and Lim respectively.

This is not the first time the Workers’ Party successfully brushed off a potential spoiler from another opposition party when taking on the PAP in a by-election. It happened in 1981, when Kenneth’s father J B Jeyaretnam of WP broke the PAP’s absolute monopoly of Parliamentary seats, despite the opposition vote being split by Harbans Singh of UPF, who won less than 1% of the votes.

I once interviewed Singapore’s most intellectually honest public intellectual, Alex Au, about his Yawning Bread blog and he said with his usual startling clarity that the opposition’s worst enemies are its supporters. I am regularly reminded of the truth of this tongue-in-cheek statement, and no more so than tonight, after the Workers’ Party’s stunning by-election victory. I came across a Facebook post vilifying a blogger for no other reason than that he had opined that the WP had been a disappointment in Parliament and that they didn’t deserve another MP yet.

One chap said simply: “kill him. burn him”. It wasn’t even an anonymous comment. In addition to his name, his Facebook profile declares proudly that he works at Rolls-Royce Aerospace. And to take the cake, it was his birthday. So here’s a WP supporter (supposedly) with a job in a respected MNC, who observes the day his mother gave birth to him by showing contempt for the life and dignity of a fellow human being who happens to have a different political view.

WP’s NCMP Yee Jenn Jong has already come out to say there’s no excuse for such behaviour, even if there is an explanation for the frustration behind it.

WP’s NCMP Yee Jenn Jong has already come out to say there’s no excuse for such behaviour, even if there is an explanation for the frustration behind it.

It is a useful reality check, I suppose. It hardly matters if the WP wins more seats and inches closer to a First World Parliament, if citizens’ political values are straight from the Stone Age.

UPDATE: The victim has made a police report. Not sure if that was necessary. I would have just asked the fellow’s employer to clarify if this kind of behaviour is in keeping with the company’s professed desire to be a good corporate citizen, and sit back and see what happens.

The obstacles to internal reform are formidable, but citizens shouldn’t discount the possibility entirely.

Picture a PAP government that lets an independent election commission draw constituency boundaries, introduces freedom of information laws and fights for equality even when it’s unpopular. This would be a PAP that committed itself to democratic processes, open government and individual rights.

In my previous blog, I said that this was the kind of PAP that I could believe in and get behind. I can’t say if such changes would arrest the growth of the opposition – probably not, since the opposition’s Parliamentary presence has been unnaturally low and is bound to rise no matter how well the government performs. But such reforms could enhance the PAP’s moral legitimacy and reduce the kneejerk negativity that currently greets its every move.

Creating a checklist for change was mainly a personal exercise to help me avoid two pitfalls as a citizen. First: naivety, which would make me satisfied with superficial changes. Second: cynicism, which would prevent me from recognising and supporting meaningful improvements.

Of course, there are fellow citizens whose visions of a better Singapore include no room for the PAP in any shape or form – and, at the other ideological extreme, people who want the PAP to stay exactly the way it is. I can only promise them greater respect for their opinions than they are likely to give me for mine (since, ironically, intolerance of differing views is a shared tendency of both the pro-PAP and anti-PAP extremes of the political spectrum – some Facebook denizens were so outraged that I could contemplate the possibility of a reformed PAP that they labelled me “closet PAP” and “whiter than white”, which I assume were meant as insults).

Sources of radical change

More thought-provoking were comments from readers who agreed with my sentiments but doubted that the PAP could ever remake itself so radically. Said one: “I am inclined to adopt your checklist as my own as it resonates well, but where we are not aligned is your optimism on the PAP’s ability and will to cross the chasm.”

I’m not optimistic either. Nevertheless, if we want radical change in the medium term – say, the next 10 years – the odds of it coming from a non-PAP government are even lower than it emanating from within the PAP.

Recent history offers some hints of where democratic change might come from. Looking at societies as different as the Soviet Union, Poland, the Philippines, South Africa, Indonesia, Egypt and Myanmar, what’s clear is that freedom must almost always be struggled for (the Kingdom of Bhutan being possibly the only example where someone with absolute power recognised he should give it up long before anyone asked him to).

It’s also clear that democratic change is sometimes instituted by those within the palace walls, and sometimes imposed only after those outside break open the gates and take over control.

What’s even more striking is that although historians can join the dots with benefit of hindsight, it is extremely difficult to look ahead and predict the path to democracy that a nation will take. People power movements that threw out seemingly immovable leaders like Suharto took most by surprise. Equally, radical reformers who transformed the establishment from within, like Mikhail Gorbachev and Thein Sein, seemed to emerge from out of the blue.

Perhaps, then, the lesson for those who want democratic change is to be steadfast about their preferred destination but agnostic about which routes will get us there. The examples of Aung San Suu Kyi and Nelson Mandela are instructive. They are heroes in the history of democratisation not only because of their moral courage but also because they kept open minds, knowing when to do business with reformers on the inside, for the larger good of their countries. Conversely, people who want change but refuse to work with elements of the old regime tend to get nowhere.

Diverse strategies

Freedom from doubt is an occupational hazard of politicians, but in reality, nobody knows what will ultimately work. Faced with irreducible uncertainty, it is foolish to place all of Singapore’s eggs in the PAP basket. Fortunately, most Singaporeans now accept this as common sense rather than as an unspeakable heresy.

Unfortunately, in the so-called new normal, too many intelligent Singaporeans seem to be oblivious to the opposite risk, of putting all our eggs in the anti-PAP basket, as if no good could ever come from the ruling party.

The same nobody-knows principle applies when deciding among different opposition strategies. Opponents of a regime are often split between more accommodationist and more belligerent strands – and it is usually difficult to predict which will be more effective. In post-war Singapore, the more radical PAP triumphed, while history would come to consign the more moderate Singapore Progressive Party to the role of rather wimpish also-rans. On the other hand, in the American civil rights struggle, the more acceptable Martin Luther King Jr. achieved what the radical Malcolm X could not.

Fast forward to today’s Singapore, and we find opposition loyalties split between the Workers’ Party and the Singapore Democratic Party. The WP seems desperate to avoid what it perceives as the self-destructive confrontational tendencies of the SDP, while SDP politicians will privately tell you that the WP has sold out – sitting pretty on its seats, afraid to take risks. Understandably, passions on both sides run high, just as they do among PAP loyalists.

The truth is that Singapore democracy is best served by different groups trying different things. Most likely, there is a complex interaction between all these forces, with more radical forces opening space for more moderate opponents, and both applying healthy pressure on incumbents.

Revolution from within?

One plausible scenario is that, pushed by opposition parties and ordinary citizens, reform-minded leaders within the PAP will persuade their comrades to undertake radical change.

Although plausible, this is not likely. Here’s where the PAP’s traditional strengths – its cohesion and internal discipline – become its Achilles’ heel. Its top leaders are selected because they share certain convictions, and it is difficult to see any of them shed those beliefs to adopt a more democratic agenda.

The PAP will also find it harder than most major parties elsewhere to reform itself from the bottom. The conventional way for new blood to take over a party is for them to come up through the ranks, developing a base within party branches, competing for influence against other contenders, and finally making a bid for the party leadership at the party convention. This open, competitive process allows would-be party leaders with bold new ideas to move from the fringes to the centre. It allows parties to regenerate and revolutionise their thinking to keep up with the times.

The PAP, however, long ago dismantled such mechanisms for internal revolution. After the break with Lim Chin Siong and the radical left, Lee Kuan Yew restructured the party, installing an impervious phalanx of cadres that would ensure that the PAP could never be captured from below. This has been part of the formula for PAP stability for the past five decades. But it could also induce paralysis.

The PAP’s best hope is that, somewhere in Singapore today, is a handful of men and women with the independence of mind, boldness of vision, and determination to serve that characterised the party’s founding generation of leaders. The PAP must hope that these individuals believe that the ruling party remains a seaworthy vessel, and that they will strive to take over its helm.

But this is where the party’s structure does not match its own best interests. The hypothetical dream team would face a Catch 22. They cannot reform the party fundamentally until they reach the top. But they cannot reach the top unless they shed their revolutionary ambitions. Thanks to the cadre system, it’s only with the blessings of the current leadership can they climb the party hierarchy – and the current leadership is unlikely to sanctify young turks with radically different views.

So, all in all, one shouldn’t be too optimistic about the PAP’s ability to remake itself. But then nobody describes politics as the science of what’s probable. It is the art of the possible. And though unlikely, perhaps PAP minds can be changed.

The case for bold reform is that this could finally enable the PAP to seize the political initiative, in a way that the current gradualism has not. The argument for doing it sooner rather than later is that the PAP has less to lose if it institutes changes while still in a position of strength, than if it waits till it’s cornered and forced to compromise with its opponents. Whether anyone in the PAP is willing and able to tread this path is the big question. If the unlikely happens, I hope enough Singaporeans will be sentient enough to see it and welcome it.

Now that the public is more assertive, it wouldn’t hurt to think about what exactly we expect from the PAP. Here’s my own wish list.

For most of 2012, Punggol made national news mainly as a showcase for the government’s prowess in public housing. There were international accolades for the Punggol Waterway district and a healthy buzz around the recently completed Treelodge@Punggol, touted as HDB’s first build-to-order eco-project.

Since mid-December, though, any Google News search, keyword punggol, would yield a more scandalous set of headlines, attesting to the PAP’s human frailty. The town’s impressive development plans are still on track. But as much as government technocrats love being left alone to tinker with their policies, they must now contend with the prospect of a high-risk by-election in the Punggol East constituency.

In that sense, the news from the Northeast was not as much of a shocker as it’s been made out to be. Sure, it was the first time the ruling party lost an MP in mid-term to an extra-marital tryst. But the episode was in keeping with the larger narrative of Singapore politics since the 2011 general election: A government of formidable capability is repeatedly forced on the defensive by a public with a penchant for picking at its flaws.

Indeed, the new default mode in Singapore politics is finding fault with the ruling party. This is not necessarily a bad thing, since the best defence against bad government is ultimately a vigilant citizenry. And in some respects, those in charge have deserved the criticism they’ve received. But, it must seem to the PAP as if there’s no policy so sound nor statement so sweet that it won’t be spat at by some section of the public.

Naturally, the abuse is fiercest from the significant minority of diehard opposition supporters who’ve come to the conclusion that Singapore would be better off if the PAP lost power. One would think that they’d be neutralised by the PAP’s own loyalists who don’t want the party to deviate too much from its traditional course – but then these supporters are rather more timid than their opponents.

At these two ends of the political spectrum, party allegiance is inelastic: attitudes towards the PAP are relatively fixed regardless of what it does. Discounting both extremes, what is more interesting is the response of the large middle ground of Singaporeans, whose support for the PAP and its policies is conditional. Such citizens set the tone for Singapore’s political culture and will determine electoral outcomes.

These Singaporeans seem to be waiting to see how the PAP responds to last year’s electoral setbacks. They can be tough customers, turning over every new government initiative with the piercing eye and sharp tongue of an auntie examining fish at a market stall run by a chap who hasn’t yet won her trust, despite his insistence that it’s all fresh and cheap.

To help her make up her own mind, she applies a mental checklist – price, springiness of flesh, redness of gills, clarity of eyes (of the fish, not the seller). The savvy shopper protects herself with a shield of skepticism, but remains open minded to the possibility that this stall may really offer the best deals in the market. If she overdid her negativity, she’d never go home with any fish.

As citizens, similarly, we might cheat ourselves of good government if our cynicism is so automatic and unthinking that we fail to support moves that are, on close inspection, in our own enlightened self-interest. Instead, we need an attitude of rational and reasoned skepticism, judging the PAP’s actions against yardsticks that we have taken the time to think through.

Such homework was less important when the PAP’s monopoly on power was as taken for granted as the fact that our MRT trains would run smoothly. Regardless of what its passengers thought, the PAP behemoth would trundle along its chosen track. Since the last election, though, PAP dominance no longer looks like a sure thing. Now, the course of Singapore politics will depend on whether people are convinced by the PAP’s internal reforms, or decide that it’s time to give another team the chance to lead.

Reforms I’d like to see

There is no universal checklist for this – it’s not like buying fish – which makes it all the more important that we make up our own minds about what exactly would satisfy us.

I’ve been mulling over this question for a while, asking myself what it would take for the PAP to win me over so completely that I would not only vote for the party but also count myself as an enthusiastic and vocal supporter. The answers I’ve arrived at may not resonate with many others, but I’m satisfied that they are consonant with my own values as a citizen.

First, I want leaders who think they know best – but are equally certain that they don’t know it all. Politicians shouldn’t run for office if they aren’t convinced they can do the job better than anyone else. But, a wise leader accepts that he might be wrong on any given decision, no matter how sincere and well intentioned he is.

So, I’d want to see the PAP going beyond platitudes about consultation and conversation. It needs to not just tolerate alternative views on a case-by-case basis, but also protect with passion the space for dissent. If it uses its power to silence criticism deemed to be unconstructive, this would indicate the hubris of a team that has deluded itself that it can escape the grip of groupthink without the check of fearless external critics.

I would tick off this box on my checklist if the PAP instituted such reforms as: creating an Ombudsman’s office; introducing open government reforms, including on the right to information; encouraging our universities to adopt guarantees of academic freedom; and taking a stand against the politics of fear, by abandoning the use of defamation suits to settle political debates and declaring a moratorium on the use of detention without trial against peaceful political opponents.

Second, I’d expect to see the PAP permitting opponents to challenge its political power on a level playing field. Top of the to-do list must be an independent election commission, such that the process of drawing electoral boundaries would be insulated from the executive branch. The national broadcaster should move towards the BBC model, with a charter requiring it to be scrupulously impartial in its coverage of politics.

A fairer system could cause the PAP to win fewer seats – but this setback would be more than compensated for by the extra legitimacy it would gain from winning those seats fair and square. After all, whatever problems the PAP currently faces in capturing hearts and minds are hardly due to the fact that it now faces four more Opposition MPs in Parliament. It is the shortage of competition, not its excess, that has made so many Singaporeans cynical.

Third, I’d like the PAP to stand up for what’s right, even if this places it a few steps ahead of the majority of Singaporeans. Already, the PAP prides itself in staying focussed on Singapore’s long-term interests even at the cost of short term popularity. However, on certain issues of principle, it has not exercised sufficient moral leadership, because it claims that the masses are not ready to follow.

I’d like to see it blazing a trail to the moral high ground, and then using its clout to pull Singaporeans up there with it. It could be more conscientious in fighting greenhouse gas emissions, and as generous as other small, wealthy countries in alleviating suffering in the world. I suspect that if it acted more idealistically, the PAP would attract many more young Singaporeans, who crave something to believe in.

Above all, though, I would want it to uphold the principle of equality. It should be defending the right of homosexuals to be treated equally, despite the objections of conservatives who wish to impose their values on others. It should not base cultural policy – including censorship of film and the internet – on the sensitivities of those with the thinnest skin, if they instead have the option simply to avert their gazes. As for our racial and religious diversity, I’d like to see the PAP publicly disavowing past statements that have made minorities feel less than equal.

Getting the rules of the game right

You may have noticed that my wish list doesn’t touch on the usual hot-button topics, like how to keep healthcare or housing affordable, or whether immigration should be tightened. I’m more concerned about the context in which decisions are made than the content of the decisions themselves.

After all, while democracy is often equated with people power, it can’t be about all of the people winning all of the time. On the contrary, what makes democracy a superior form of government is that it provides a peaceful and civilised way to lose – it encourages those defeated in a debate or an election to accept that they have lost legitimately to the will of the collective, within a system that respects their rights.

I’m also mindful of the fact that many of the policy choices facing Singapore are genuinely difficult. When the government speaks of tough trade-offs, it’s not kidding. I may have strong views on many policy issues, but I have to concede that other citizens may have different positions, and that my own knowledge on many subjects remains woefully inadequate.

So, I don’t need to be on the winning side of every policy debate before I support the ruling party. I just need to be able to believe in the rules of the game. That’s why my criteria emphasise open, fair and principled rules for managing disagreements.

Some of the items on my checklist may seem radical, but I don’t consider them beyond the PAP’s reach. They are not like asking the Republican Party in the US to turn its back on the National Rifle Association, or getting Israel’s Likud to embrace Hamas. I don’t see anything I’ve proposed as fundamentally incompatible with the PAP’s pragmatic position of doing what works for Singapore.

At the same time, such moves would be sufficiently bold to silence those who doubt the PAP’s sincerity in reforming itself. The party has tried to win over Singaporeans through incremental change, and it clearly hasn’t been enough.

If it continues in the current mode, many middle-of-the-road Singaporeans will continue to seize every opportunity to bring the government down a notch. People will deal with the government like villagers who “throw sticks at trees to knock their fruit down to the ground”.

There’s apparently a Malay word for that action. Aptly enough, the verb is – punggol.

Is the PAP capable of such change?

Many of the comments I’ve received here and through Facebook have said that the PAP would not be able to reform itself. I’m not optimistic either, but feel it’s important to acknowledge the possibility, no matter how slim, that radical change will come from within. Read my next blog.

Page 3 of 4

Powered by WordPress & Theme by Anders Norén